The Lemnian Deed: A Text World Approach – Part 2

Then Iphinoe led him through a beautiful porch and seated him on a gleaming chair before her mistress, who turned her eyes from him, maiden cheeks flushed red. Still, despite her embarrassment, she addressed him with well-crafted words.

A.R. 1.788-92

To reach the poem’s second account of the Lemnian Deed, we are skipping a hundred and sixty-six lines of verse containing further developments in the narrative which could affect the engaged reader’s attitude towards the women and thus the possible emotional response to Hypsipyle’s account here (See Adjusting the dynamics of narrative interest). Nor was that initial narratorial exposition analysed in Part 1 especially damning as Edward George also observed almost fifty years ago.

In the flash-back narrative, then, the poet does two things, which reinforce each other: he renders the murder story more objective and harder to participate in by the scholarly note [digression on future fate of Thoas and aetiology of the island’s naming, see Part 1, Fig. 3], and he contrives to protect the reader from feeling the full horror of the women’s guilt by reticence and euphemism. The Lemnian women are more wretched than culpable. They elicit compassion, but compassion based on selection and arrangement of the facts.

Mindful then of these mitigating factors, we’ll press on here with text-world creation and the paradigmatic analysis.

Hypsipyle, Storyteller

It is at lines 793f. then that Jason hears in the queen’s own words what has happened on Lemnos, and the reader (an extradiegetic but ratified discourse participant) hears a character-version of events already summarised by the narrator. For Jason, the speech has an argument function. It is intended to explain the current peculiar situation (why are all the inhabitants of the island female?), to provide assurances against any threat and to persuade the Argonauts to enter the city. Her direct speech has a basic rhetorical pattern: the opening ‘why do you stay outside the city…’ (793) is answered at the end of her speech by ‘[therefore] do not stay outside the city’ (833).

When the two characters begin their discourse, Hypsipyle’s opening words establish some common ground. The participants are both on Lemnos but the women are in the city and the Argonauts remain outside. Why are the Argonauts lingering? Are they worried about the Lemnian men? Hypsipyle offers assurances to her addressee who might then create a quite minimal text-world – in the present the Lemnian men have emigrated (she identifies them with the adjective ἐπινάστιοι ‘strangers living in another land’ and are farming in Thrace. The qualification πυροφόρους ‘wheat-bearing’ might suggest a reason – there’s good soil on the mainland. The reader, however, might struggle to reconcile this text-world with the ones created previously.

What Hypsipyle goes on to do is provide a backstory of her own, one to explain why the men are now in Thrace, and it’s one for which she provides a guiding introduction herself: Κακότητα δὲ πᾶσαν ἐξερέω νημερτές, ἵν’ εὖ γνοίητε καὶ αὐτοί, ‘I will speak truthfully the entire evil that you yourselves might know it well.’ The verb γνοίητε is a second-person plural as her addressee is representative of all the Argonauts but might also be read as an invitation (or challenge) to the reader to reflect on new evidence and reappraise our evaluations.

Each time an enactor speaks, a world-switch transports readers of the text directly to that enactor’s origo for as long as the speech is ongoing.

Hypsipyle begins by offering her version of the habitual state of affairs on Lemnos under her father Thoas’ rule. The first word of line 798 εὖτε is a temporal deictic ‘when’ and the verbs ‘was ruling, were raiding, were bringing back’ are in the past continuous tense. She switches back to a time when Lemnian raids on Thrace were the norm (Fig. 5 below, text-world 2).

εὖτε Θόας ἀστοῖσι πατὴρ ἐμὸς ἐμβασίλευε,

τηνίκα Θρηικίην οἵ τ’ ἀντία ναιετάουσι

[800] δήμου ἀπορνύμενοι λαοὶ πέρθεσκον ἐναύλους

ἐκ νηῶν, αὐτῇσι δ’ ἀπείρονα ληίδα κούραις

δεῦρ’ ἄγον. Οὐλομένης δὲ θεᾶς πορσύνετο μῆτις (μῆνις)

Κύπριδος, ἥ τέ σφιν θυμοφθόρον ἔμβαλεν ἄτην·

A.R. 1.798-803

When Thoas my father was ruling the townsfolk, the men of the country used to go and from their ships raid the homes of the people who inhabit Thrace opposite us, fetching here measureless plunder along with the girls themselves. The plan (rage) of the destructive goddess, Cypris, was being accomplished – she cast into the men a mind-perverting infatuation.

The change to the status quo comes with the entry of Cypris into her account and a decisive action performed by the goddess in the simple past tense. She cast folly into the men (Fig. 5 above, text-world 3). This folly (ἄτη) is qualified as θυμοφθόρος, the adjective intensive and attributive, usually rendered ‘mind-perverting’ but more literally ‘life-destroying.’ Jason might construct his text-world using the former translation but the reader under the influence of the earlier exposition might lean to the latter. Or both.

I’ve allowed myself just the one intertext, one which is dependent on a variant in the manuscript tradition and one which shows the difference a single consonant can make to the reading. μῆτις is a plan, something devised. Hypsiple announced her own μῆτις in the Lemnian assembly before asking who could devise a better one. It’s a keyword in an epic in which manipulation not strength of arms proves to be the route to success. μῆνις, on the other hand, is rage. Odysseus then or Achilles?

μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος | οὐλομένην (Il. 1.1-2)

Sing goddess, the destructive rage of Achilles, son of Peleus.

Both narrator and character accounts include Cypris but whereas the narrator follows the trail back to her as the divine origin (See Part 1, Fig. 2), Hypsipyle brings the source Cypris to the head of her own account, revises the narrator’s χόλος αἰνός (614) as μῆνις, and thus begins on this reading) by echoing the beginning of the epic tradition. Accepting the reading μῆνις, is the storytelling queen attempting a miniature Lemnian Iliad?

δὴ γὰρ κουριδίας μὲν ἀπέστυγον ἔκ τε μελάθρων

[805] ᾗ ματίῃ εἴξαντες ἀπεσσεύοντο γυναῖκας,

αὐτὰρ ληιάδεσσι δορικτήταις παρίαυον,

σχέτλιοι. Ἦ μὲν δηρὸν ἐτέτλαμεν, εἴ κέ ποτ’ αὖτις

ὀψὲ μεταστρέψωσι νόον·

A.R. 1.804-8

For of course they began to violently hate their lawfully-wedded wives and yielding to folly, drove them out from the homes. Instead, they were sleeping with captive women won by the spear, hard-hearted men. And of a surety we endured a long time, hoping at some point far off they’d change their minds again.

The trigger event creates this new status quo which initially finds us on very familiar ground as the opening δὴ γὰρ κουριδίας μὲν of 804 is a repeat of 611 ‘for of course lawfully-wedded…’ but adding the evaluation ματίῃ εἴξαντες ‘yielding to folly’ instead of the narrator’s ‘hating them’. In place of the harsh lust that they had for their captured women (611) Hypsipyle supplies the verb παρίαυον (806), and repeats the narrator’s ληιάδεσσι (612) but qualifies it with δορικτήταις: ‘they were sleeping with captives won by the spear’. Her spear-won women contrast with lawfully-wedded wives and begins a series of oppositions when she fills in the blanks in the narrator’s account and evaluates the Lemnian men as the narrator does not. σχέτλιοι she calls them – hard-hearted, resistant to compassion. It reoccurs as an attribute of Eros in a narrator apostrophe to the god himself in the Argonautica’s final book.

σχέτλι᾽ Ἔρως, μέγα πῆμα, μέγα στύγος ἀνθρώποισιν,

ἐκ σέθεν οὐλόμεναί τ᾽ ἔριδες στοναχαί τε γόοι τε

A.R. 4.445-6

Hard-hearted Eros, a great evil, great abomination for humans, from you come destructive quarrels, and groans and laments.

Following her evaluation of the Lemnian men, Hypsipyle switches to an inclusive first person plural ‘we endured it for a long time’ (which we might contrast with the way the narrator singled her out as exceptional) and the reason given for this endurance creates a Boulomaic modal world ‘hoping that they would at some point far off change their minds again.’

This is a true story.

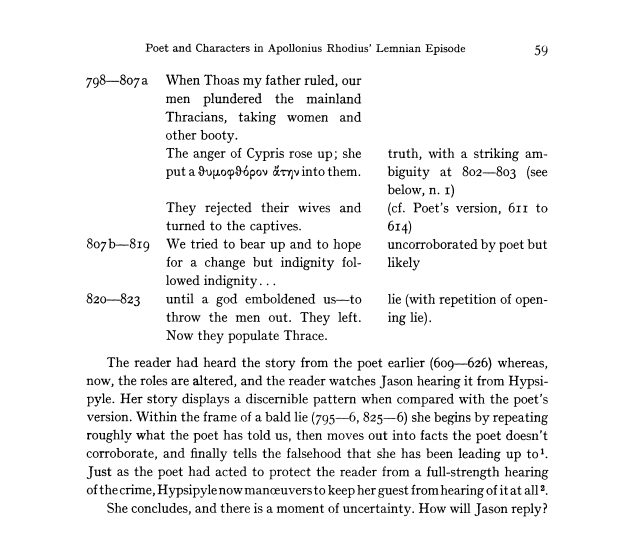

But that boulomaic world is immediately superseded by a detailed account of the subsequent reality as she claims to have experienced it (or as George (1972: 59) comments, ‘uncorroborated but likely’, see partial reproduction of his speech table below). Unlike the Argonautica’s narrator, Hypsipyle was there.

τὸ δὲ διπλόον αἰεί

πῆμα κακὸν προύβαινεν. Ἀτιμάζοντο δὲ τέκνα

[810] γνήσι’ ἐνὶ μεγάροις, σκοτίη δ’ ἀνέτελλε γενέθλη·

αὔτως δ’ ἀδμῆτες κοῦραι, χῆραί τ’ ἐπὶ τῇσι

μητέρες, ἂμ πτολίεθρον ἀτημελέες ἀλάληντο·

Οὐδὲ πατὴρ ὀλίγον περ ἑῆς ἀλέγιζε θυγατρός,

εἰ καὶ ἐν ὀφθαλμοῖσι δαϊζομένην ὁρόῳτο

[815] μητρυιῆς ὑπὸ χερσὶν ἀτασθάλου· οὐδ’ ἀπὸ μητρός

λώβην ὡς τὸ πάροιθεν ἀεικέα παῖδες ἄμυνον,

οὐδὲ κασιγνήτοισι κασιγνήτη μέλε θυμῷ·

Ἀλλ’ οἶαι κοῦραι ληίτιδες ἔν τε δόμοισιν

ἔν τε χοροῖς ἀγορῇ τε καὶ εἰλαπίνῃσι μέλοντο,

[820] εἰσόκε τις θεὸς ἄμμιν ὑπέρβιον ἔμβαλε θάρσος,

ἂψ ἀναερχομένους Θρῃκῶν ἄπο μηκέτι πύργοις

δέχθαι, ἵν’ ἢ φρονέοιεν ἅπερ θέμις, ἠέ πῃ ἄλλῃ

αὐταῖς ληιάδεσσιν ἀφορμηθέντες ἵκοιντο.

A.R. 1.808-823

But the evil affliction ever advanced and doubled. In homes, legitimate children were dishonoured, and a bastard race began to rise. And just as they were, unmarried girls and widowed mothers wandered neglected throughout the city. Neither did a father trouble at all about his own daughter, even if he saw with his eyes her being cleaved by the hands of a wicked stepmother, nor did, as before, sons ward shameful insults from their mothers, nor did brothers hold care in their heart for a sister. But the captive girls alone were a concern, in homes, in dances, in the meeting-place, in solemn feasts, until some god cast into us an overwhelming courage to receive them no longer within the towers when they returned again from the Thracians, in order that either they would either recall again what was right or they would head off with their captives and go to some other place. But they then demanded the children, all that were male and remained in the city, and went back to the snowy plowland of Thrace where they dwell even to this day.

This is not (as far as 819 at least when the unnamed god intervenes to inspire resistance) in contradiction to the version of the male narrator. He simply didn’t mention any of it as he advanced instantly from jealousy to destruction (616-7), giving no material with which to create such a world.

Her Lemnian text-world has almost all the same enactors. Omissions include the fishermen and Oenoe for Hypsipyle’s character knowledge does not extend to awareness of her father’s fate. Bringing up any mention of his escape would be in any event run counter to her purpose. Without reference to other futures or locations, her world is more temporally and spatially compact than the narrator’s.

On the other hand, her world has more relations between the enactors which the narrator did not invite the reader to consider, it takes place over a period of time, and there are more locations within Lemnos itself with which to sketch out the city and civic life. In Hypsipyle’s focalisation of events, there is more emotional colouring for that world and its offshoots e.g. there’s a character-accessible hypothetical world (at least I think it’s hypothetical) ‘even if before his eyes the father saw his daughter being killed at the hands of a wicked step-mother.’

The Lemnian world of the character-witness is a more detailed and complex one. A whole string of relational processes are attached to the Lemnian women, Lemnian men, and Thracian women in lines 808f. and a lot of them are identifying.

Legitimate children are dishonoured and bastards produced (809-10, future generation are in danger!).

Both unmarried girls and mothers are made vagrant (811-2, young and old affected alike).

Fathers neglect daughters, sons neglect mothers and brothers neglect sisters (813-7, family connections are made and broken down by the verbs).

Slave-girls supplant the women in homes, markets, dances and feasts (818-19, in private and in public spaces the Thracian women are the new Lemnian women).

This is the grim world she creates, the world which the women find the courage to change (lines 820f.). Again divine intervention serves a plot-advancing function. Some god cast (ἔμβαλε is simple past tense) overwhelming courage into us – again inclusive). What follows in the Greek syntax is another purpose clause, in order that either a or b. There are two possible outcomes proposed both dependent on the Lemnian men’s reaction to the women taking a stand – either a return to the old world of Lemnos or the current world of Lemnos (as Hypsipyle has outlined it).

The great deed that the women feared the Argonauts would discover has been retold as a divinely-inspired revolt against oppression. The loose end is tied up when the men take the latter option.

Οἱ δ’ ἄρα θεσσάμενοι παίδων γένος ὅσσον ἔλειπτο

[825] ἄρσεν ἀνὰ πτολίεθρον, ἔβαν πάλιν ἔνθ’ ἔτι νῦν περ

Θρηικίης ἄροσιν χιονώδεα ναιετάουσιν.

A.R. 1.824-6

But straightaway demanding the children, all that were male and remained in the city, they went back to the snowy plowland of Thrace, and there they dwell even to this day.

Hypsipyle switches from the backstory to her present status quo (and shifts location to Thrace for the moment) with spatial and temporal deictics, ἔνθ’ ἔτι νῦν περ ‘there even to this day’, (the first of five occurrences in the poem of the phrase in this sedes, used by both primary and character narrators when making temporal jumps), and a present tense verb ναιετάουσιν ‘they are dwelling’.

In returning to the present time, Hypsipyle has also circled round to her preliminary remarks though the Thracian fields are now snowy rather than wheat-bearing, perhaps to compare unfavourably with the fertile fields of Lemnos. She concludes her speech with an extraordinary offer of kingship and with instructions for Jason to repeat her story and invitation of welcome to the Argonauts but I’ll finish here with a note on the narrator’s framing of her speech.

Ἴσκεν, ἀμαλδύνουσα φόνου τέλος, οἷον ἐτύχθη

ἀνδράσιν·

A.R. 1.834-5

So she spoke, glossing the slaughter which happened to the men.

ἀμαλδύνουσα φόνου τέλος translates as ‘softening/mitigating the coming to pass of the slaughter.’ With φόνος the narrator refers back to his own account of Lemnian prehistory – the entire male population was erased to prevent retribution for a miserable slaughter (λευγαλέος φόνος, 619). Her speech was introduced as being spoken with words intended to charm, words well-crafted (μύθοισι προσέννεπεν αἱμυλίοισιν, 792) and is closed with a reminder of what the narrator stated as actually having happened. Her extended narration is thus framed and coloured by references to its (and her) manipulative intent.

Yet in early epic the verb ἀμαλδύνω only ever means destroy. It is used in the Iliad of the destruction of physical objects for which no trace now remains. Thanks to her speech, no trace of the murder and the narrator’s account has been replaced. Jason is persuaded and will persuade the Argonauts. Lemnos will be repopulated by the soon-to-be impregnated Lemnian women, the Argonauts will sail on none the wiser and thanks to the world(s) Hypsipyle well-crafts, these Lemnian women do get away with murder.

Blumberg suggests that the two accounts of the island’s history allow the reader to distinguish Hypsipyle’s lies from the truth. As we see here, the double version also enables us to compare the cunning of the poet with that of his character.

Supplementing George’s observation, I would add that even this rudimentary application of Text World Theory can better enable us to make that comparison. Whilst there is obvious overlap between observations made here and those made previously in Adjusting the dynamics of narrative interest, the undertaking to isolate enactors and locations, identify deictics and label processes to create diagrams of some of the text-worlds available to the reader of these expositions has in itself yielded more connections and made some of the existing comparisons and contrasts more striking. There is more to be done of course and with greater sophistication but the initial results are, to my mind, fruitful.

References

Gavins, J. (2007) Text World Theory: An Introduction, Edinburgh.

George, E. V. (1972) ‘Poet and Characters in Apollonius Rhodius’ Lemnian Episode’, Hermes 100: 47-62.

Illustration by William Russell Flint in Sir Thomas Malory’s ‘Le Morte d’Arthur: The Book of King Arthur and his Noble Knights of the Round Table’, (1910-11).

Research interests include intertextuality, indeterminacies, reader-experience and reader-manipulation.