The Lemnian Deed: A Text World Approach – Part 1

‘First at the head of legendary crime stands Lemnos. People shudder and moan, and can’t forget – each new horror that comes we call the hells of Lemnos.’

(Aeschylus, Choephoroi, 631-4, trans. Fagles).

In Adjusting the dynamics of narrative interest, I considered how different distributions of expositional material in regard to the ‘Lemnian Deed’ could affect the first-time reader’s experience of and response to the Lemnian women. Here I’m taking a different approach to two expositional sections of this Argonautic episode and (following Gavins 2007) constructing the text-worlds created in the course of processing the expositions; the intention being to set out what elements the expositions have in common and where they differ in the elements we process when creating their text-worlds. For example, what, if any, are the dominant elements? Is there an element, e.g. spatial or temporal, that we have to work harder to process? What elements are underdetermined? What type of relational processes (Gavins 2007: 43) do we find in each and in what mode? In this first part of two, I’ll set out the text-worlds we create when processing the narrator’s preliminary exposition, then in part 2 tackle those created when reading the later character exposition of the Lemnian ruler Hypsipyle.

Approaching Lemnos

Whilst narratorial exposition of the Lemnian Deed occurs lines 609 following, I’m beginning with the eight lines preceding this to create the text-world from which we then switch when arriving at Lemnos.

ἦρι δὲ νισσομένοισιν Ἄθω ἀνέτελλε κολώνη

Θρηικίη, ἣ τόσσον ἀπόπροθι Λῆμνον ἐοῦσαν,

ὅσσον ἐς ἔνδιόν κεν ἐύστολος ὁλκὰς ἀνύσσαι,

ἀκροτάτῃ κορυφῇ σκιάει, καὶ ἐσάχρι Μυρίνης.

[605] τοῖσιν δ᾽ αὐτῆμαρ μὲν ἄεν καὶ ἐπι κνέφας οὖρος

πάγχυ μάλ᾽ ἀκραής, τετάνυστο δὲ λαίφεα νηός.

αὐτὰρ ἅμ᾽ ἠελίοιο βολαῖς ἀνέμοιο λιπόντος

εἰρεσίῃ κραναὴν Σιντηίδα Λῆμνον ἵκοντο.

A.R. 601-8

At dawn, the Thracian mountain of Athos appeared on the horizon as they journeyed which with its topmost peak shades Lemnos, though it is as far away as a well-equipped merchant-ship could travel by midday, and even as far as Myrine. That whole day until dark a very strong favourable wind was blowing for them, and the ship’s sails had been stretched tight. But with the rays of the sun and the wind fading as one, they reached by oar rocky Sintian Lemnos.

The first line here begins with a temporal deictic that enables us to establish a time of day for the ensuing action: ‘at dawn’. Then the first verb we encounter is in the simple past tense, ‘the prototypical tense for narrated texts describing scenes and events at spatial and temporal distance’ (Gavins 2007: 39). Mount Athos appeared before them as they were in the act of moving/travelling. Our enactors the Argonauts are referenced three times in this selection of text, obliquely via that present participle and the demonstrative pronoun ‘for them’ before in the final line they assume agency and reach Lemnos. Mount Athos, subject of two main verbs here, is a prominent object. The other objects are nautical (ship, sails, oars) or elemental (sun, rays, wind) and likely present the reader with no problems of comprehension. But that merchant-ship appears in a relative clause which employs a tense shift and a world switch.

Athos casts a shadow (present tense, casts now as it did then). Lemnos is (now) as far away as a merchant-ship could reach (hypothetical path, future-orientated). This is a world-switch to the time of the narrator in whose now Mount Athos still casts far its shadow, Lemnos is where it then was and where a merchant-ship of his time could reach by midday. With the use of the present continuous tense, the origo shifts momentarily from the Argonauts to the narrator looking from the third century BCE to the time of myth. Only for two lines, however, as 605-6 summarise a day’s sailing and 607-8 with the fading of sun and wind advance us to dusk and set the Argonauts within reach of the island.

We’ve been following the ship’s path from l. 580 through the Aegean seascape and now have an endpoint. What else can we say about Lemnos? The world-building elements are fairly minimal. As the Argonauts arrive, it’s dusk and the weather is calm. Lemnos is rocky and Sintian and there’s a place on it called Myrine. And then comes a world-switch.

Last Year on Lemnos

Ἔνθ’ ἄμυδις πᾶς δῆμος ὑπερβασίῃσι γυναικῶν

νηλειῶς δέδμητο παροιχομένῳ λυκάβαντι.

A.R. 1.609-10

There, all at once the population had been killed and ruthlessly by the transgressions of the women in the preceding year.

The adverb ἔνθα is a spatial deictic, our cue to project our viewpoint to the island itself. However, as we continue to process the text, we find that this viewpoint is not shared by the Argonauts. The participants in this discourse are the Argonautica’s narrator and the readers. Two new enactors are introduced: the population and the women who destroyed that population. Following the spatial shift comes a temporal shift which marks this information exchange as a flash-back. The tense of δέδμητο ‘had been slain’ is pluperfect. The island had been (partially) depopulated prior to the Argonauts’ arrival. Line 610 ends with a temporal expression which narrows down this past time and enables us to refine the world-switch as ‘Last Year on Lemnos’.

Time – Recent Past (year before fictive present of narrative)

Location – Lemnos

Enactors – Lemnian Men and Women

Then we switch again temporally, shifting back before the decisive action for explication of what motivated that action.

Δὴ γὰρ κουριδίας μὲν ἀπηνήναντο γυναῖκας

ἀνέρες ἐχθήραντες· ἔχον δ’ ἐπὶ ληιάδεσσι

τρηχὺν ἔρον, ἃς αὐτοὶ ἀγίνεον ἀντιπέρηθεν

Θρηικίην δηιοῦντες, ἐπεὶ χόλος αἰνὸς ὄπαζε

Κύπριδος, οὕνεκά μιν γεράων ἐπὶ δηρὸν ἄτισσαν.

Ὢ μέλεαι ζήλοιό τ’ ἐπισμυγερῶς ἀκόρητοι,

οὐκ οἶον σὺν τῇσιν ἑοὺς ἔρραισαν ἀκοίτας

ἀμφ’ εὐνῇ, πᾶν δ’ ἄρσεν ὁμοῦ γένος, ὥς κεν ὀπίσσω

μή τινα λευγαλέοιο φόνου τίσειαν ἀμοιβήν.

A.R. 1.611-619

For, of course, the men rejected their lawful wives, hating them; they held a coarse lust for the captive girls they brought back themselves when raiding Thrace on the opposite shore. The dread anger of Cypris was pressing them hard, because for a long time they deprived her of her due honours. Unhappy women, in jealousy sadly unsated! Not only did they destroy their own husbands and the women alongside them in their beds, but every male Lemnian alike, to avoid paying any retribution in the future for the miserable murder.

As can be see in Fig. 2 above, this summary exposition already involves three temporal (and one locational) world-switches, switches which as readers we make with little difficulty.

In the space of just two paragraphs, readers of The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency must construct at least five separate text-worlds in order to conceptualise the shifting time-zones of the text. However, while this text-world structure may appear complex under analysis, it is important to remember that the participants in a discourse-world have the ability to create multitudinous text-world networks in an instant and without significant cognitive effort. The majority of discourses which extend beyond a sentence or two will contain multiple world-switches, and discourse participants are normally able to monitor and manage their varying deictics without difficulty. The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, for example, is a popular novel and by no means a ‘difficult’ read for the majority of competent adult readers.

Here we switch from the slaughter back to the act of rejection which motivated the slaughter. For of course the men rejected their lawfully-wedded wives. Certain expectations are being placed upon the reader of this exposition by the narrator’s employment of interactional particles.

Δή ‘of course’ is best described as a (bidirectional) ‘evidential’ or ‘cooperative’ particle. It marks that, according to the speaker, an utterance arises as self-evident from knowledge (contextual or extra-textual) which both discourse participants have at their disposal. Simply put, a speaker indicates with δή that he is stating the obvious or asking an obvious question. The particle establishes interpersonal consensus (speaker and addressee are on common ground), reduces the possibility of challenges, and solicits empathy.

For the Argonautic narrator it is a means then to invite our collusion by reminding us of the knowledge and therefore common ground we share.

δή makes an important contribution to what I have elsewhere called “the rhetoric of shared tradition”, an almost conspiratory narrative fiction in which the narratees are reminded of what they already know, because they know the same stories as the narrator – according to the fiction upheld in the Argonautica: from hearing poems. Of course, to the ancient readers of the author Apollonius “they say” meant “they write”, and one may also wonder how many readers ever entered this poem with all the knowledge that it presents as ‘obvious’. This, however, is a guestion of an entirely different order. The narrator Apollonius addresses his narratees as peers.

And the immediately following word in the Greek text γάρ ‘for’ is another interactional particle: ‘a speaker provides background information to what he has just told, anticipating a request for motivation, explanation or elaboration from his addressee’ (Cuypers 2005: 67-8). Essentially, the narrator Apollonius addresses the narratees as peers who know stuff, whether or not they actually do. For of course (as we all know well) the men rejected their wives.

From being subject and active as transgressive killers, the switch back in time reduces the women to an earlier status of discarded object. A clear opposition is laid out in the actions of the men; a spurning of wives is set against an ongoing desire for a new enactor – captive women. Where did they come from? In the relative clause we switch again, further back temporally and across spatially; these women were taken in a raid on mainland Thrace.

Then another switch and a new enactor as the narrator moves from object of desire to the divine source driving the emotion – ‘The dread anger of Cypris (Aphrodite) was pressing them hard because for a long time they deprived her of her due honours.’ ‘They’ is wonderfully non-specific – there’s no pronoun in the Greek, just the third person plural past tense verb ἄτισσαν. Then having been transported to Lemnos in advance of the Argonauts and gone back in stages to the source, we return via an exclamation (the Argonautic narrator is subjective and intrusive) to repetition of the deed.

The men are here their husbands destroyed in their beds and the motivation for killing all the males is given in a purpose clause. It was done in order to avoid a world in which the women suffer retribution. Which takes us back to the narrator’s initial labelling of the killing as ὑπερβασία, a transgression, something for which payment is due. There are no details to help imagine how such the act was orchestrated. The entire male population and all the captive girls are efficiently killed in a bed and two verses. Instead we are given an exception and two new named enactors as our initial text-word expands.

Οἴη δ’ ἐκ πασέων γεραροῦ περιφείσατο πατρός

Ὑψιπύλεια Θόαντος ὃ δὴ κατὰ δῆμον ἄνασσε·

λάρνακι δ’ ἐν κοίλῃ μιν ὕπερθ’ ἁλὸς ἧκε φέρεσθαι,

αἴ κε φύγῃ.

A.R. 1.620-3

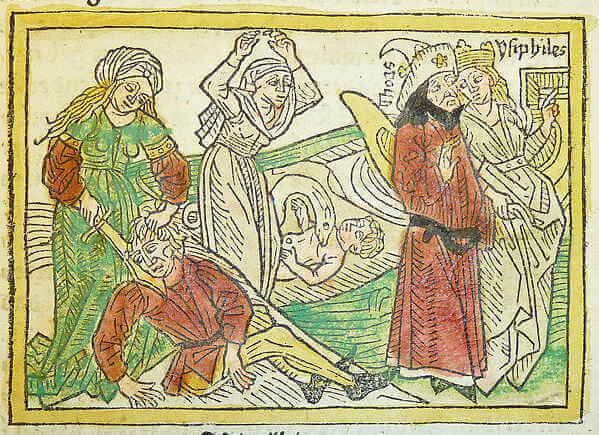

Alone out of them all, Hypsipyle, the daughter of Thoas, saved the life of her old father, who was then ruler of the people. She put him in an empty chest to be carried across the sea, in the hope he might escape.

In the female versus male dichotomy that the Argonautic narrator maps out in this backstory, Hypsipyle, daughter of Thoas, bridges the divide. ‘She alone out of all saved her aged father.’ Then there is an expansion on Thoas’ social status, ‘he who ruled the people.’ It is the position she subsequently takes up. Father and daughter are subsequently linked several times in the episode: she wears his armour (637-8); she sits in the assembly on her father’s seat (667); Iphinoe, the Lemnian messenger, tells the Argonauts that Hypsipyle, daughter of Thoas sent her (712-3).

Here the boulomaic world she hopes for in which her father survives contrasts with the one the Lemnian women imagined – the future male revenge world whose possibility motivated the mass slaughter. What the narrator does next is supply for the reader an immediate confirmation of Hypsipyle’s hope. The narration charts the onward journey of the father she put in a box and set on the sea.

Кαὶ τὸν μὲν ἐς Οἰνοίην ἐρύσαντο

πρόσθεν, ἀτὰρ Σίκινόν γε μεθύστερον αὐδηθεῖσαν

νῆσον, ἐπακτῆρες, Σικίνου ἄπο, τόν ῥα Θόαντι

Νηιὰς Οἰνοίη Νύμφη τέκεν εὐνηθεῖσα.

A.R. 1.623-6

And he was dragged ashore by fisherman at the island known then as Oenoe but in later times called Sicinus, after the Sicinus whom the Naiad Oenoe bore after making love to Thoas.

The locational world-switch transitions to a temporal one (πρόσθεν … μεθύστερον, ‘then … but later’). Thoas met a water-nymph Oenoe, had a son with her and her eponymous island was/will be (at some unspecified point between storytime and narrator-time) renamed after the son, Sicinus; a Thoas future-world which the narrator contrasts with the situation of the women back on Lemnos who have adopted the now vacated male military and agricultural roles in Lemnian society. That concludes the narrator’s exposition so far as the deed itself is concerned. Looking at the relational processes which occur in the narrator’s summary exposition (Fig. 4 below), we see they are for the most part intensive and attributive.

There are not a great many attributive elements. The Lemnian women are introduced as lawfully-wedded. Then in the narratorial exclamation they are unhappy and unsated. The anger of Cypris is dread. The slaughter is miserable. The chest is hollow. The qualification of passion/lust as coarse/prickly is possibly the only attributive which might strike the reader as uncommon. Then there are the identifying intensive processes: the women are wives and the men are husbands; Hypsipyle is a daughter and Thoas is a father (as well as being old, another attributive intensive process).

Key relationships are established, some evaluations made, and considering this is summary discourse between the narrator and ourselves, we should perhaps not expect much more than the bare bones, especially if it’s being implied that we know this material already. Having processed this, in Part 2 we’ll apply the same methodology to the character exposition of Hypsipyle and compare the resultant worlds created and processes involved.

References

Cuypers, M. (2005) ‘Interactional Particles and Narrative Voice in Apollonius and Homer’ in Beginning from Apollo: studies in Apollonius Rhodius and the Argonautic tradition, ed. A. Harder and M. Cuypers, Leuven: 35-69.

Gavins, J. (2007) Text World Theory: An Introduction, Edinburgh.

Research interests include intertextuality, indeterminacies, reader-experience and reader-manipulation.