Struck by Eros: Experiencing the genesis of Medea’s passion.

Some say that a host of cavalrymen is the fairest thing on the black earth, some a host of infantry, others of ships: I say it is what one loves. (Sapph. 16. 1-4, trans. Campbell)

At the opening of the third book of the Argonautica with the heroes’ arrival at Colchis the narrator finally invokes a Muse to stand by his side, but not Calliope, the Muse of Epic.

εἰ δ᾽ ἄγε νῦν, Ἐρατώ, παρά θ᾽ ἵστασο, καί μοι ἔνισπε,

ἔνθεν ὅπως ἐς Ἰωλκὸν ἀνήγαγε κῶας Ἰήσων

Μηδείης ὑπ᾽ ἔρωτι· σὺ γὰρ καὶ Κύπριδος αἶσαν

ἔμμορες, ἀδμῆτας δὲ τεοῖς μελεδήμασι θέλγεις

[5] παρθενικάς· τῶ καί τοι ἐπήρατον οὔνομ᾽ ἀνῆπται.

A.R. 3.1-5

Come now, Erato, stand by and tell me

from there how to Iolcus Jason brought the fleece

through Medea’s love. For you also in Cypris’ field

have a share, and with thoughts of love you charm

the virgin girls; therefore to you is attached a name of love.

Erato, the Muse of love poetry, sharing Aphrodite’s (here Cypris) sphere of influence, charms the unwed girls with love-cares. θέλγω is to charm, to bind with a spell. It affects one’s reason (νόος). The Lovely One has the lovely name which ‘reinforces her fitness for the job she has been summoned to do’ (Hunter 1989: 96). Previously I’ve looked at Medea’s dream but here I’m stepping further back in Book 3 to review the conception of her passion and those epic and lyric intertexts fused into its construction.

Its genesis is on Olympus where Hera and Athena conspire with Aphrodite to enlist Eros ‘a creature of lyric, epigram, and other “minor” genres’ to the cause (Feeney 1991: 78). Once bribed, the god takes flight for Colchis whilst simultaneously the chosen ambassadors of the Argonauts make their way to the city on foot. But before we meet Medea, an image from the plain of Troy:

τὸν δ᾽ ὃ γέρων Πρίαμος πρῶτος ἴδεν ὀφθαλμοῖσι

παμφαίνονθ᾽ ὥς τ᾽ ἀστέρ᾽ ἐπεσσύμενον πεδίοιο,

ὅς ῥά τ᾽ ὀπώρης εἶσιν, ἀρίζηλοι δέ οἱ αὐγαὶ

φαίνονται πολλοῖσι μετ᾽ ἀστράσι νυκτὸς ἀμολγῷ,

ὅν τε κύν᾽ Ὠρίωνος ἐπίκλησιν καλέουσι.

[30] λαμπρότατος μὲν ὅ γ᾽ ἐστί, κακὸν δέ τε σῆμα τέτυκται,

καί τε φέρει πολλὸν πυρετὸν δειλοῖσι βροτοῖσιν·

ὣς τοῦ χαλκὸς ἔλαμπε περὶ στήθεσσι θέοντος.

Il. 22.25-32

The old man Priam saw Achilles first as he rushed over the plain, shining bright as the star that comes late in the summer. Among the many stars its rays shine clear in the deep of night and they name it Orion’s Dog. It shines the brightest but is an evil sign and brings much fever to wretched mortals. So gleamed the breast of Achilles in its glittering bronze.

In the Iliad, when Achilles blazed over Troy’s plain in fatal pursuit of Hector, it was Priam who first spied the man who had caused and would continue to cause him so much pain. Priam, the father who would kneel to kiss those man-slaying hands, sees Achilles first because Priam should see Achilles first. In the Argonautica, it is Medea who sees the Argonauts first.

τοὺς δ᾽ ἔχον ἀμφίπολοί τε καὶ Αἰήταο θύγατρες

ἄμφω, Χαλκιόπη Μήδειά τε. τῇ μὲν ἄρ᾽ οἵ γε

ἐκ θαλάμου θάλαμόνδε κασιγνήτην μετιοῦσαν.

[250] Ἥρη γάρ μιν ἔρυκε δόμῳ· πρὶν δ᾽ οὔ τι θάμιζεν

ἐν μεγάροις, Ἑκάτης δὲ πανήμερος ἀμφεπονεῖτο

νηόν, ἐπεί ῥα θεῆς αὐτὴ πέλεν ἀρήτειρα.

καί σφεας ὡς ἴδεν ἆσσον, ἀνίαχεν.

A.R. 3.247-253

The handmaids lived in those rooms and both daughters of Aeetes, Chalciope and Medea. It was Medea they saw; she was going from room to room looking for her sister. Hera, you see, was detaining her at home. Before then she hardly ever frequented the palace, but all day attended Hekate’s temple since she was herself the priestess of the goddess. And when she saw them draw nearer, she screamed.

A short ekphrasis on the fantastical palace unfolds into a list of occupants from which Medea steps out, finally emerging into the poem’s narrative present as a player. She is the first to see them. Why? Hera, by detaining her, has forced the encounter. The narrator offers a little additional information for the reader’s benefit. Usually she spent her days in Hekate’s temple; for us a reminder that her occupation, her precocious talent for sorcery, is the reason for her involvement in the plot. Medea sees them first because Medea should see them first. Her reaction is a scream, one of alarm not yet of pain, a scream that alerts Chalciope, her sister.

Chalciope shares a reunion scene with her sons now travelling with the Argonauts. King Aeetes and his queen Eidyia arrive. Servants prepare a feast. Medea saw the Argonauts first but not yet him. It is left for Eros to pick out first Jason and then her when amidst the ensuing hubbub, the god also arrives. Indeed, he adds to the disorder; he is ‘full of turmoil’ (τετρηχώς, 276), likened to a gadfly among the young grazers. Finding his mark, Eros takes up his position and aims.

ὦκα δ᾽ ὑπὸ φλιὴν προδόμῳ ἔνι τόξα τανύσσας

ἰοδόκης ἀβλῆτα πολύστονον ἐξέλετ᾽ ἰόν.

[280] ἐκ δ᾽ ὅγε καρπαλίμοισι λαθὼν ποσὶν οὐδὸν ἄμειψεν

ὀξέα δενδίλλων· αὐτῷ ὑπὸ βαιὸς ἐλυσθεὶς

Αἰσονίδῃ γλυφίδας μέσσῃ ἐνικάτθετο νευρῇ,

ἰθὺς δ᾽ ἀμφοτέρῃσι διασχόμενος παλάμῃσιν

ἧκ᾽ ἐπὶ Μηδείῃ· τὴν δ᾽ ἀμφασίη λάβε θυμόν.

A.R. 3.278-284

And quickly, at the base of the doorpost in the vestibule, Eros strung his bow and took an arrow – fresh, mournful – from his quiver. From there, with swift steps he crossed the threshold unobserved, looking keenly around. Then crouching down small by Jason’s legs, he placed the arrow’s notches in the centre of the bowstring, and pulling it straight apart with both hands, he shot at Medea. Speechless amazement seized her heart.

The presentation of the shot itself I’ve discussed previously in its use of scene and ellipsis (see Measuring Arrows in Time) so here will only repeat Hunter’s observation: ‘The monosyllabic verb after a lengthy presentation (278-83) and the central punctuation “dividing” two references to Medea mark the speed and stunning effect of the shot’ (1989: 129). From aim to effect with ‘no “the arrow struck home”’ (M. Campbell 1983: 27). That central punctuation elides the hit, its force is instant and as Hunter notes its effect is stunning.

ἀμφασίη ‘speechlessness’ occurs only once in the Iliad (and once in the Odyssey). In the Iliad, it takes hold of Antilochus who must shake free of it in order to deliver news of Patroclus’ death to Achilles (see Death in the Iliad: Reports and Responses).

δὴν δέ μιν ἀμφασίη ἐπέων λάβε, τὼ δέ οἱ ὄσσε

δακρυόφι πλῆσθεν, θαλερὴ δέ οἱ ἔσχετο φωνή.

Il. 17.695-6

For a long time speechlessness seized hold of him, his eyes filled with tears, and his strong voice was checked.

The arrow renders Medea likewise speechless but the god laughs.

[285] αὐτὸς δ᾽ ὑψορόφοιο παλιμπετὲς ἐκ μεγάροιο

καγχαλόων ἤιξε· βέλος δ᾽ ἐνεδαίετο κούρῃ

νέρθεν ὑπὸ κραδίῃ φλογὶ εἴκελον. ἀντία δ᾽ αἰεὶ

βάλλεν ἐπ᾽ Αἰσονίδην ἀμαρύγματα, καί οἱ ἄηντο

στηθέων ἐκ πυκιναὶ καμάτῳ φρένες· οὐδέ τιν᾽ ἄλλην

[290] μνῆστιν ἔχεν, γλυκερῇ δὲ κατείβετο θυμὸν ἀνίῃ.

A.R. 3.282-290

Back again he darted from the high-roofed hall,

laughing loudly; the arrow burned in the girl,

underneath her heart, like a flame. Ever

she shot sparkling eyes at Aeson’s son, and in distress

prudent thoughts were blown from her chest; no other

memory she held but flooded her heart with sweet pain.

καγχαλόων is the same cackling response he made on beating (cheating?) Ganymede at dice (A.R. 3.124). ‘The disjunction between the kitschy antics of Eros and the suffering of the human is allowed to find its place in the larger disjunction between the inhuman, self-sufficient ease of the gods and the baffled pain of the human experience’ (Feeney 1991: 82). Achilles made a similar observation.

ὡς γὰρ ἐπεκλώσαντο θεοὶ δειλοῖσι βροτοῖσι

ζώειν ἀχνυμένοις· αὐτοὶ δέ τ᾽ ἀκηδέες εἰσί.

Il. 24.525-6

For thus the gods spun for wretched mortals a life of sorrow, but careless is their own existence.

In the minor key of Iliadic plotting, everyone is a victim. Of the leading players, it is Achilles who takes the longest to learn this truth about the rules that write the story of his life, and by implication of our own; and only when he does is the plot complete.

Men live in grief – the gods without care. There is such a tension here; Eros flapping back to Olympus for his reward whilst his victim Medea is struck dumb with the first pangs of a destructive passion. The reader of the Argonautica familiar with fifth century Athenian drama knows how and where this affair might end. Two centuries earlier, the chorus of her Euripidean tragedy (431 BCE) sang of passion beyond moderation and love’s all-conquering weaponry. At the conclusion of Medea’s first confrontation with Jason in the play, the Corinthian women offered their lyric response.

ἔρωτες ὑπὲρ μὲν ἄγαν ἐλθόντες οὐκ εὐδοξίαν

[630] οὐδ᾽ ἀρετὰν παρέδωκαν ἀνδράσιν. εἰ δ᾽ ἅλις ἔλθοι

Κύπρις, οὐκ ἄλλα θεὸς εὔχαρις οὕτως.

μήποτ᾽, ὦ δέσποιν᾽, ἐπ᾽ ἐμοὶ χρυσέων

τόξων ἀφείης ἱμέρῳ

[635] χρίσασ᾽ ἄφυκτον οἰστόν.

E. Med. 627-35

Loves that come to us in excess bring no good name or goodness to men. [630] If Aphrodite comes in moderation, no other goddess brings such happiness. Never, o goddess, may you smear with desire one of your ineluctable arrows and let it fly against my heart [635] from your golden bow! (trans. Kovacs)

And in another Euripidean tragedy, the prize-winning Hippolytus of 428 BCE, the women of Troezen voice the same fear of love’s excess in language containing several points of contact with our Argonautic text.

[525] Ἔρως Ἔρως, ὁ κατ᾽ ὀμμάτων

στάζων πόθον, εἰσάγων γλυκεῖαν

ψυχᾷ χάριν οὓς ἐπιστρατεύσῃ,

μή μοί ποτε σὺν κακῷ φανείης

μηδ᾽ ἄρρυθμος ἔλθοις.

[530] οὔτε γὰρ πυρὸς οὔτ᾽ ἄστρων ὑπέρτερον βέλος,

οἷον τὸ τᾶς Ἀφροδίτας ἵησιν ἐκ χερῶν

Ἔρως ὁ Διὸς παῖς.

E. Hipp. 525-34

[525] Eros, god of love, distilling liquid desire down upon the eyes, bringing sweet pleasure to the souls of those against whom you make war, never to me may you show yourself to my hurt nor ever come but in due measure and harmony. [530] For the shafts neither of fire nor of the stars exceed the shaft of Aphrodite, which Eros, Zeus’s son, hurls forth from his hand. (trans. Kovacs)

The tragic arrow that flies from the Cyprian’s bow is inescapable (ἄφυκτος) and smeared with longing (ἵμερος). The attribute attached to Eros’ epic arrow is πολύστονος (279), ‘mournful’ or ‘much-sighing’. The potential of an arrow to deliver many sighs does occur once in the poem’s epic models. In the Iliad, Teucer’s arrow which pierces the Trojan Kleitos in the back of the neck is also πολύστονος (Il. 15.451). But in our context the wound is supernatural, figurative, and the pain it inflicts is the pain of longing.

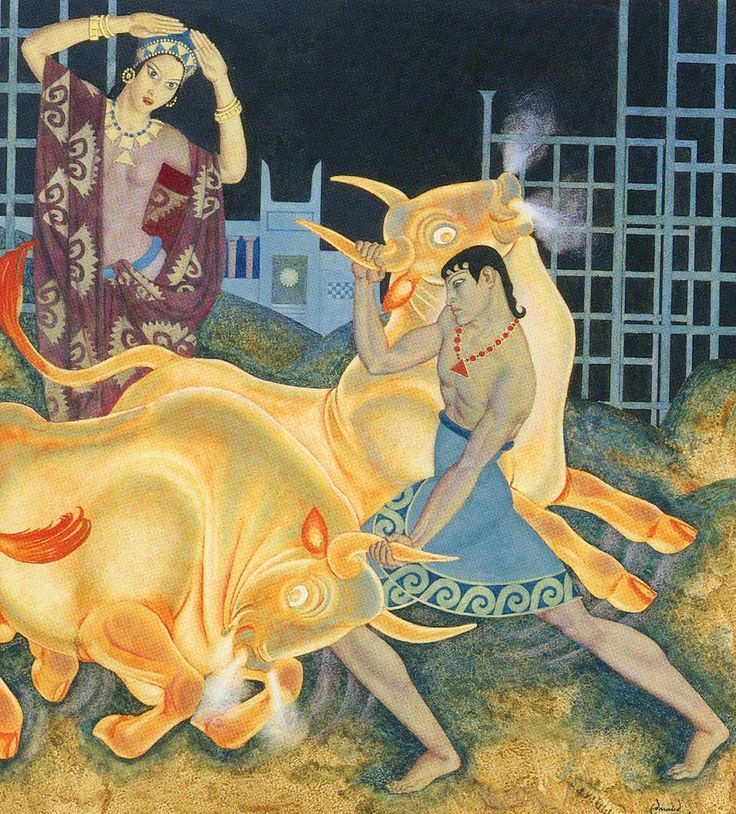

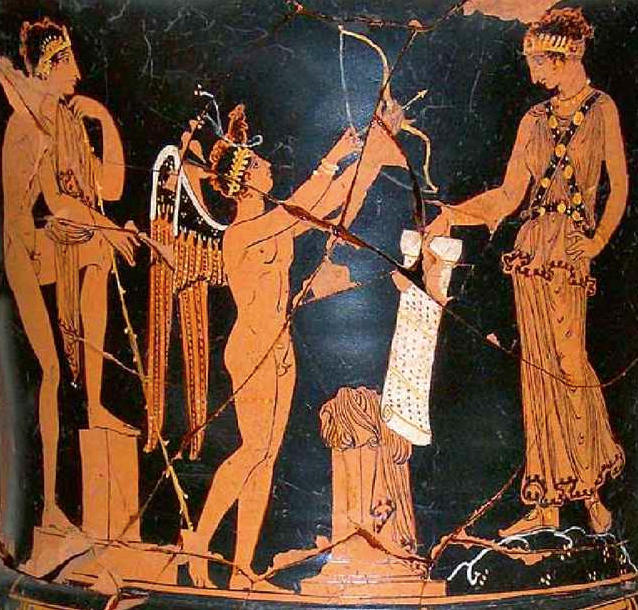

‘Ever she shot sparkling eyes at Aeson’s son’. Jason – Eros – Medea; Sicilian red-figure krater, c.350 BCE. © Regional Aeolian Archaeological Museum.

The impact has shaken her θυμός. West (1997: 232) writes, ‘In Homer both thoughts and emotions are commonly located in the θυμός, properly the “spirit”, but often most conveniently rendered as “heart”; it alternates with the more physiological φρένες and κραδίη.’ In this selection we have references to all three. The shaft burns its way down under the girl’s κραδίη. Medea, κούρη, does not yet know what is happening to her.

καί οἱ ἄηντο | στηθέων ἐκ πυκιναὶ καμάτῳ φρένες (288-9)

‘They were blown [over the line] out of her chest, the crowded [jumbled?] by her pain thoughts (φρένες).’ The word-order simulates her upheaval – the explosive run-over, the separation of body and mind … deep breaths, Medea.

Conceptual Metaphors

The lyric ‘I’ of Sappho 31 declares a similar physical response to the sight of the beloved.

τό μ’ ἦ μὰν | καρδίαν ἐν στήθεσιν ἐπτόαισεν (Sappho 31, 5-6)

That, I swear, flutters the heart in my chest.

However, before exploring some lyric intertexts potentially in play here, I wish to outline those conceptual metaphors also evident and within the reading experience of most if not all of the poem’s possible readers.

Traditionally, ‘That man is a shark’ would be seen as a metaphor whereas ‘That man is like a shark’ would be seen as a simile: a distinction based only on surface realisation. However, the same conceptual metaphor underlies both forms: THE MAN IS A SHARK (conceptual metaphors are always written in small capitals like this). The distinction is useful because the conceptual metaphor THE MAN IS A SHARK can underlie several possible surface expressions of the metaphor: ‘that man is a shark’, ‘shark-man’, ‘he was in a feeding frenzy’, ‘he’s always got to keep moving forward’, ‘he’s sharking’ and so on.

Now there’s an obvious conceptual metaphor underlying the presentation of Eros wounding Medea: LOVE IS WAR. But let’s look again at lines 285-90.

[285] αὐτὸς δ᾽ ὑψορόφοιο παλιμπετὲς ἐκ μεγάροιο

καγχαλόων ἤιξε· βέλος δ᾽ ἐνεδαίετο κούρῃ

νέρθεν ὑπὸ κραδίῃ φλογὶ εἴκελον. ἀντία δ᾽ αἰεὶ

βάλλεν ἐπ᾽ Αἰσονίδην ἀμαρύγματα, καί οἱ ἄηντο

στηθέων ἐκ πυκιναὶ καμάτῳ φρένες· οὐδέ τιν᾽ ἄλλην

[290] μνῆστιν ἔχεν, γλυκερῇ δὲ κατείβετο θυμὸν ἀνίῃ.

A.R. 3.282-290

Back again he darted from the high-roofed hall,

laughing loudly; the arrow burned in the girl,

underneath her heart, like a flame. Ever

she shot sparkling eyes at Aeson’s son, and in distress

prudent thoughts were blown from her chest; no other

memory she held but flooded her heart with sweet pain.

The arrow burned in the girl, underneath her heart, like a flame. The arrow is desire and desire is fire. The verb-construction ‘burned’ presents the source ‘fire’ from which the target ‘love’ can be referenced. The conceptual metaphor LOVE IS FIRE is then reinforced in its most visible form, in the simile ‘like a flame.’ The mapping of fire onto love continues into the next line when Medea’s sparkling eyes make repeat retaliatory shots (LOVE IS WAR) at Jason. She fires the fire back at him. The onset of her erotic love is mapped then as heat and light but in the verb-constructions of lines 289-90 it becomes more expansively elemental.

In his analysis of the Event Structure Metaphor in D. H. Lawrence’s ‘Song of a Man Who Has Come Through’, Peter Crisp connects that conceptual system with the conceptual metaphor EMOTIONS ARE NATURAL FORCES of which lack of emotional control is a ‘standard entailment’ (Crisp 2003: 102). Here that loss of control is rendered in that passive construction when bereft of her agency thoughts are blown out of her chest. This is emotional change conceptualised as blowing wind: she looks at Jason and the sight takes her breath away. As a challenge for my own reader, feel free to add in the comments those everyday expressions which map onto the same conceptual metaphors. The final metaphorical mapping here is activated by the verb κατείβετο ‘flooded’. The elemental range mapping erotic love has flowed from fire through air to water, from a burning heart to a helpless spirit drowning in a sweet pain.

Epic Love and Lyric Echoes

Now, I’d contend that the presentation of the onset of passion presents the modern adult reader no difficulties of comprehension (at least in translation) and that the metaphorical mapping above is well within their experiential range. That said, what follows requires a different reader – a learned reader required by a learned poet to realise the love-echoes latent within the text.

The Homeric epics are undoubtedly the Argonautica’s models (both modello codice and modello esemplare) but as David Campbell (1983: 3) has observed ‘[the Homeric narrator] generally avoids the erotic and uses only the most reticent language for sexual union when he does mention it. Although he has the language to express desire, he nowhere describes the feelings, the unhappiness or torment, of someone in love.’ Eroticism is not entirely absent, of course, and a memorable exception is Hera’s seduction of Zeus in Iliad 14.

ὡς δ᾽ ἴδεν, ὥς μιν ἔρως πυκινὰς φρένας ἀμφεκάλυψεν (Il. 14.294).

‘And when he saw her, desire enfolded his prudent thoughts’: Zeus sees and is smitten by the sight (and in distress prudent thoughts were blown from her chest). He admits he’s desperate for sex.

οὐ γάρ πώ ποτέ μ᾽ ὧδε θεᾶς ἔρος οὐδὲ γυναικὸς

θυμὸν ἐνὶ στήθεσσι περιπροχυθεὶς ἐδάμασσεν,

Il. 14. 315-6

‘For never before has desire for a goddess or a woman flooded over and subdued the heart in my chest.’

ἔρως overcomes (δαμάζω) even the king of heaven (and nothing else did she remember but flooded her heart with sweet pain). Personified, Eros appears in Hesiod’s Theogony as one of the first of the gods, a driving force in the proliferation of life.

ἠδ᾽ Ἔρος, ὃς κάλλιστος ἐν ἀθανάτοισι θεοῖσι,

λυσιμελής, πάντων δὲ θεῶν πάντων τ᾽ ἀνθρώπων

δάμναται ἐν στήθεσσι νόον καὶ ἐπίφρονα βουλήν.

Hes. Th. 120-22

And then Eros, fairest among the deathless gods, a loosener of limbs, who overcomes thought and prudent counsel in the hearts of all gods and mortals.

Eros is a potent god who like Sleep and Death loosens the limbs. The lyric poets of Archaic Greece appropriated such epic formula and imagery and adapted it to suit their first-person voices. Apollonius’ presentation of erotic love owes much to their innovations.

The arrow bores through Medea to lodge beneath her heart. The poet Archilochus (fl. c.650 BCE Paros) had expressed the idea of a burrowing desire. Iambics frame the fragment’s hexameter.

δύστηνος ἔγκειμαι πόθωι,

ἄψυχος, χαλεπῆισι θεῶν ὀδύνηισιν ἕκητι

πεπαρμένος δι’ ὀστέων.

Archil. 193

Wretched I lie in desire, lifeless, pierced through the bones by grievous pains, thanks to the gods.

(trans. Campbell)

The dead lover is likened to a dead warrior. Because of πόθος (the longing for the absent lover) his bones are pierced by pain. ‘The language comes in part from epic … but Archilochus’ theme is love not war (D. Campbell 1983: 5, though LOVE IS WAR).’ In Archil. 191, the poet speaks of ἔρως coiling around the heart (ὑπὸ καρδίην) and stealing reason (φρένας) from his breast (ἐκ στηθέων).

τοῖος γὰρ φιλότητος ἔρως ὑπὸ καρδίην ἐλυσθεὶς

πολλὴν κατ’ ἀχλὺν ὀμμάτων ἔχευεν,

κλέψας ἐκ στηθέων ἁπαλὰς φρένας

Archil. 191

Such was the passion for love that curled up under (my) heart and shed a great mist over (my) eyes, robbing (my) breast of its tender wits.

(trans. Campbell)

Eros has taken the poet’s wits, just as the same emotion took Zeus’ and just as the same god took Medea’s. The liquid quality evident in the flooding of their reason also occurs in the poetry of Alcman (fl. C7th BCE Sparta).

Ἔρως με δηὖτε Κύπριδος ϝέκατι

γλυκὺς κατείβων καρδίαν ἰαίνει

Alcm. 59a

Love once more, thanks to the Cyprian,

sweetly pours and warms my heart.

This lyric love is warm [LOVE IS FIRE] and sweet, a trickling desire welcome to Alcman (the desire Aphrodite stirred in the Argonauts and the Lemnian women followed epic convention, Κύπρις γὰρ ἐπὶ γλυκὺν ἵμερον ὦρσεν, A.R. 1.850) whereas the emotion flooding here into Medea is ἀνία ‘sorrow’. Sweetness and sorrow is a combination observed by Sappho (c.620-570 BCE Lesbos).

Ἔρος δηὖτέ μ’ ὀ λυσιμέλης δόνει,

γλυκύπικρον ἀμάχανον ὄρπετον.

Sapph. 130

Once again Love, the loosener of limbs, shakes me, that sweet-bitter, irresistible creature.

(trans. Campbell)

Again that epithet λυσιμέλης applied to Eros (as already seen in Hesiod and Archilochus) but the compound γλυκύπικρος ‘bittersweet’ is first attested here. Her Eros is also ἀμάχανον, ‘unmanageable’, an observation that the troubled Medea will soon endorse. David Campbell (1983: 18) remarks on the freshness Sappho brings with the verb δόνει ‘used by Homer of the battering of the wind’ but here applied to the battering of Love [EMOTION IS ELEMENTAL]: ‘She sees love’s assault as both physical and mental.’

Note also as in the fragment of Alcman the occurrence of the compound δηὖτέ ‘look again/why again’. The lyric desire, imbued with striking vitality, is momentary. These poets will love again, praise again and blame again their loves consistent only in their reinvention. Medea’s affliction is enduring and passion’s flame burns through the following simile.

Love is a Disease

ὡς δὲ γυνὴ μαλερῷ περὶ κάρφεα χεύατο δαλῷ

χερνῆτις, τῇ περ ταλασήια ἔργα μέμηλεν,

ὥς κεν ὑπωρόφιον νύκτωρ σέλας ἐντύναιτο

ἄγχι μάλ᾽ ἐζομένη· τὸ δ᾽ ἀθέσφατον ἐξ ὀλίγοιο

[295] δαλοῦ ἀνεγρόμενον σὺν κάρφεα πάντ᾽ ἀμαθύνει·

τοῖος ὑπὸ κραδίῃ εἰλυμένος αἴθετο λάθρῃ

οὖλος ἔρως·

A.R. 3.291-7

As a woman scatters twigs around blazing wood,

a working woman, whose care is spinning wool,

that in her house at night she may prepare a bright flame,

sitting very close; and wondrously from the tiny brand

the flame rises up and destroys all the twigs together –

So, wrapped around her heart, it burnt in secret

Destructive Love.

When the battle outside Troy raged in stalemate, a comparison was made with the scales of wool and weights a woman measured while she worked to feed her children (Il. 12.433f.). There are (pointedly) no children here. The woman, alone in the night, seeks warmth and light (love?) but the fire consumes itself. χερνῆτις (292) ‘working woman’ picks up the notion of toil in κάματος (289, translated as ‘distress’ but also ‘weariness’) while foreshadowing a grim future beyond the epic’s confines: the exiled princess cut off from her family in an alien land (visions of Corinth will be later reinforced by a second simile of a working woman, A.R. 4.1062f.).

And as the woman is caught out by the sudden blaze, so too this innocent Medea cannot act against the secret flame that is growing within and feeding upon her. The simile ‘may be regarded as a positive affirmation at the very outset that ἔρος is essentially an externally imposed, uncontrollable force with the power to destroy quickly and without warning’ (M. Campbell 1983: 28). Yet the internal flame has visible surface symptoms.

ἁπαλὰς δὲ μετετρωπᾶτο παρειὰς

ἐς χλόον, ἄλλοτ᾽ ἔρευθος, ἀκηδείῃσι νόοιο.

A.R. 3.297-8

Her soft cheeks paled then turned red again, her mind in anguish.

She pales. She blushes. She blushes. She pales. Medea is in torment. ‘[ἔρευθος] occurs in situations ranging from the loss of innocence at the inception of sexual desire to a state of violence arising from passionate emotions’ (Pavlock 1990: 30; it was also Hypsipyle’s reaction to seeing Jason in Myrine).

Hunter detects in χλόος a medical flavour and given that ἀκήδεια is a medical term for weariness/torpor, he suggests ‘the verse gives a “clinical” description.’ κάματος (289) is also used of pain brought about by illness. And returning to πολύστονος (279), the epithet was also applied in the first book of the Iliad to the hearts of the Argives enduring the plague brought about by the onslaught of the archer-god Apollo. Arrows and disease – Eros has infected the poem.

Such is Medea’s physical and mental state as the banquet begins and its conclusion brings no relief.

θεσπέσιον δ᾽ ἐν πᾶσι μετέπρεπεν Αἴσονος υἱὸς

κάλλεϊ καὶ χαρίτεσσιν· ἐπ᾽ αὐτῷ δ᾽ ὄμματα κούρη

[445] λοξὰ παρὰ λιπαρὴν σχομένη θηεῖτο καλύπτρην,

κῆρ ἄχεϊ σμύχουσα· νόος δέ οἱ ἠύτ᾽ ὄνειρος

ἑρπύζων πεπότητο μετ᾽ ἴχνια νισσομένοιο.

A.R. 3.443-7

Like a god, he stood out among them all, the son of Aeson

In his beauty and his grace, and the girl kept glancing at him

From the side of her bright veil and admired him,

While her heart smouldered in pain. And her spirit as in a dream

Crawled and flew after his tracks as he went.

Sappho could have made an accurate diagnosis of her condition.

φαίνεταί μοι κῆνος ἴσος θέοισιν

ἔμμεν’ ὤνηρ, ὄττις ἐνάντιός τοι

ἰσδάνει καὶ πλάσιον ἆδυ φωνεί-

σας ὐπακούει

[5] καὶ γελαίσας ἰμέροεν, τό μ’ ἦ μὰν

καρδίαν ἐν στήθεσιν ἐπτόαισεν,

ὠς γὰρ ἔς σ’ ἴδω βρόχε’ ὤς με φώναι-

σ’ οὐδ’ ἒν ἔτ’ εἴκει,

ἀλλ’ ἄκαν μὲν γλῶσσα †ἔαγε λέπτον

[10] δ’ αὔτικα χρῶι πῦρ ὐπαδεδρόμηκεν,

ὀππάτεσσι δ’ οὐδ’ ἒν ὄρημμ’, ἐπιρρόμ-

βεισι δ’ ἄκουαι,

†έκαδε μ’ ἴδρως ψῦχρος κακχέεται† τρόμος δὲ

παῖσαν ἄγρει, χλωροτέρα δὲ ποίας

[15] ἔμμι, τεθνάκην δ’ ὀλίγω ’πιδεύης

φαίνομ’ ἔμ’ αὔται·

ἀλλὰ πὰν τόλματον ἐπεὶ †καὶ πένητα†

Sapph. 31

That man seems to me to be the equal of the gods who sits opposite you and close by hears your sweet words and lovely laughter: this, I swear, makes my heart pound within my breast; for when I glance at you for a moment, I can no longer speak, my tongue (is fixed in silence?), a thin flame at once runs under my skin, I see nothing with my eyes, my ears hum, sweat flows down me, trembling seizes me all over, I am paler than grass and I seem to be not far short of death. But all can be endured, since … (trans. Campbell).

‘She cannot, she finds, speak or see or hear, fever and chills fasten on her body, her blood rushes from her head, she is near fainting, she is near death (Johnson 1982: 39).’ The fire, the pallor, the sickness in the loved one’s presence – Apollonius is in her debt.

θεσπέσιον δ᾽ ἐν πᾶσι μετέπρεπεν Αἴσονος υἱὸς

κάλλεϊ καὶ χαρίτεσσιν· ἐπ᾽ αὐτῷ δ᾽ ὄμματα κούρη

[445] λοξὰ παρὰ λιπαρὴν σχομένη θηεῖτο καλύπτρην,

κῆρ ἄχεϊ σμύχουσα· νόος δέ οἱ ἠύτ᾽ ὄνειρος

ἑρπύζων πεπότητο μετ᾽ ἴχνια νισσομένοιο.

A.R. 3.443-7

θεσπέσιον (443) is the embedded focalisation of the watching Medea; to her eyes this stranger is divine. Sappho 31 begins φαίνεταί μοι κῆνος ἴσος θέοισιν ‘that man seems to me to be equal to the gods’. Apollonius cannot reproduce the vigour and song of lyric discourse by returning the lyric ‘I’ to the epic ‘she’, but he has created possibilities. A Medea struggling with her emotions, allowed to voice her anxieties, to approximate something that is like what she feels, might not be the voice of lyric making the personal universal, the present the eternal, but it is a wonderfully blended creation.

In the hall, Medea watches her stranger as another young princess had watched hers on the Scherian shore. There when Odysseus had washed away the grime of the sea, Athena poured grace upon him and turned the head of his unlikely saviour, the princess Nausicaa (κάλλεϊ καὶ χάρισι στίλβων· θηεῖτο δὲ κούρη, Od. 6.237). An echo of Odysseus’ Phaeacian saviour merges with others behind Medea’s veil. One is Hecabe and her reaction to the sight of Hector’s body dragged through the dust ‘and from her she flung her shining veil’ (ἀπὸ δὲ λιπαρὴν ἔρριψε καλύπτρην, Il. 22.406), another is Penelope’s languid entrance into the Odyssey, when by the door she wept hearing Phemius’ song ‘holding her shining veil in front of her face’ (ἄντα παρειάων σχομένη λιπαρὰ κρήδεμνα, Od. 1.334). A girl’s wish for a bridegroom blended with a mother’s lament for a son and a wife’s pain for a husband lost at sea.

The text, however, just as readily weaves in the strands of its own creation for Medea burns on. The participle σμύχουσα is formed from the verb σμύχω ‘burn in a slow smouldering fire’ and so the metaphor continues: the burning love the arrow lit under her heart – the working woman burning twigs – the heart now smouldering in pain.

Focus continues to shift within the hexameter, closing in on her heart then out with her thought now struggling now soaring like a dream, νόος δέ οἱ ἠύτ᾽ ὄνειρος | ἑρπύζων πεπότητο μετ᾽ ἴχνια νισσομένοιο (446-7). A final Homeric sounding in this section:

ἀλλὰ τὰ μέν τε πυρὸς κρατερὸν μένος αἰθομένοιο

δαμνᾷ, ἐπεί κε πρῶτα λίπῃ λεύκ᾽ ὀστέα θυμός,

ψυχὴ δ᾽ ἠύτ᾽ ὄνειρος ἀποπταμένη πεπότηται.

Od. 11.220-22

the fire in all its fury burns the body down to ashes

once life slips from the white bones, and the spirit,

rustling, flitters away … flown like a dream. (trans. Fagles)

The flames have spread to the intertexts and the image of the funeral pyre darkens the metaphor. Love is fire and fire consumes. The words are spoken by the shade of Odysseus’ mother Anticleia. Once fire has destroyed the body, the spirit leaves and ‘like a dream flutters and flies away’.

τό μ’ ἦ μὰν | καρδίαν ἐν στήθεσιν ἐπτόαισεν – That, I swear, flutters the heart in my chest.

χλωροτέρα δὲ ποίας | ἔμμι, τεθνάκην δ’ ὀλίγω ’πιδεύης | φαίνομ’ ἔμ’ αὔται – I am paler than grass and I seem to be not far short of death.

Her soft cheeks paled then turned red again, her mind in anguish.

By Love Enthralled

Χαλκιόπη δὲ χόλον πεφυλαγμένη Αἰήταο

[450] καρπαλίμως θάλαμόνδε σὺν υἱάσιν οἷσι βεβήκει.

αὔτως δ᾽ αὖ Μήδεια μετέστιχε· πολλὰ δὲ θυμῷ

ὥρμαιν᾽, ὅσσα τ᾽ Ἔρωτες ἐποτρύνουσι μέλεσθαι·

A.R. 3.449-2

Chalciope, wary of Aeetes’ wrath,

went quickly to her chamber with her sons.

Likewise Medea followed – turning over in her heart

the many things which love-spirits rouse to be a care.

Jason has left for the ship but trailing behind Chalciope, Medea’s head is swirling. On the Homeric use of ὁρμαίνω, Vivante (1997: 28) writes: ‘these acts or states are rendered in that they take place, they happen and their effect is seen spreading out to their pertinent organs.’ Lines 451-2 recall Penelope’s apprehension as she descends to test the stranger’s claim (πολλὰ δέ οἱ κῆρ | ὥρμαιν᾽, Od. 23.85-6) but the ‘love-spirits’ confound the echo. ‘The god’s name is also the name of his effect … Apollonius veers from the creature who acts in the narrative and causes the passion, towards an available metaphorical range of reference (Feeney 1991: 83).’ Medea, Hekate’s priestess, is not yet aware of the forces acting secretly upon her. A stranger has come and she can’t stop thinking about him.

προπρὸ δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ὀφθαλμῶν ἔτι οἱ ἰνδάλλετο πάντα,

αὐτός θ᾽ οἷος ἔην, οἵοισί τε φάρεσιν ἧστο,

[455] οἷά τ᾽ ἔειφ᾽, ὥς θ᾽ ἕζετ᾽ ἐπὶ θρόνου, ὥς τε θύραζε

ἤιεν·

A.R. 3.453-6

And before her, in front of her eyes, everywhere he still appeared,

himself, what he was like, how he was dressed,

what he said, how he sat on his chair, how he went

to the door.

Note the polyptoton – οἷος … οἵοισί … οἷά – she has been studying him over dinner, picking out details. On ἔειφε (455), Hunter (1989: 148) comments, ‘Medea “sees” Jason speaking, as well as “hearing” what he said.’ Watching the movement of his lips, her absorption seems total. A detailed scrutiny to be played back over and over. The recollection moves from the visual.

ἐν οὔασι δ᾽ αἰὲν ὀρώρει

αὐδή τε μῦθοί τε μελίφρονες, οὓς ἀγόρευσεν.

A.R. 3.457-8

Continuously in her ears

his voice stirred and the words he spoke sweet to the hearing.

His words ring in her ears. They are μελίφρονες ‘sweet to the mind’. When Dream whispers in Agamemon’s ear, ‘sweet to the mind’ is an epithet of sleep, (μελίφρων ὕπνος, Il. 2.34). Hector declines Hecabe’s offer of wine ‘sweet to the mind’ lest it weaken his warrior spirit (μή μοι οἶνον ἄειρε μελίφρονα πότνια μῆτερ, Il. 6.264). Jason spoke to Aeetes with charming words (μειλιχίοισιν (385), as did Hypsipyle to Jason). Medea, unlike her father, was susceptible to his charm. Heroic usage – lyric perception:

‘hears your sweet words and lovely laughter’ (Sapph. 31.3-6, trans. Campbell).

From her fixation comes concern, ostensibly for Jason but perhaps also for herself, for those feelings she is struggling to express. The tears come (462), then, for the first time, we hear her speak (and for her statistics, see Speakers and Speeches in the Argonautica).

Speech gives a character’s inner life a voice, and in the Homeric epics, which avoid extensive narratorial use of indirect discourse and psychological commentary, it is the only device allowing the reader any deep access to that inner life. No character of significance to the plot of the Iliad, no character whose private experience invites more than momentary reader interest (as for example in a necrology), is denied a speech.

‘τίπτε με δειλαίην τόδ᾽ ἔχει ἄχος; εἴθ᾽ ὅ γε πάντων

[465] φθίσεται ἡρώων προφερέστατος, εἴτε χερείων,

ἐρρέτω. ἦ μὲν ὄφελλεν ἀκήριος ἐξαλέασθαι.

ναὶ δὴ τοῦτό γε, πότνα θεὰ Περσηί, πέλοιτο,

οἴκαδε νοστήσειε φυγὼν μόρον· εἰ δέ μιν αἶσα

δμηθῆναι ὑπὸ βουσί, τόδε προπάροιθε δαείη,

[470] οὕνεκεν οὔ οἱ ἔγω γε κακῇ ἐπαγαίομαι ἄτῃ.’

A.R. 3.464-70

‘Why does this grief hold me, foolish child? If he dies

and he is the best of all heroes, or the worst,

let him go! No, would that he escaped unharmed!

Yes, only may this happen, dear goddess, daughter of Perses,

may he return home, escaping his doom, but if his destiny

is to be slain by the bulls, this first may he learn,

that I at least take no joy in his terrible fate.’

She questions the reason for her pain and attempts to purge it; εἴθ᾽ ὅγε πάντων | φθίσεται ἡρώων προφερέστατος, εἴτε χερείων, | ἐρρέτω (464-6) – ‘What if he dies and he is the best of all heroes, perhaps the worst, let him go!’ Aeetes did not accept Argus’ reference (φέριστον | ἡρώων, 347-8) but Medea did and she is starting to lean, in her eyes Jason is a hero.

ἐρρέτω (466) – She is feeling something and trying to push it out. Calypso made the same response upon hearing the will of Zeus (Od. 5.139). ‘Let him go’ is a tame translation. Odysseus, to gain his νόστος, must be released by the nymph. The magic of the witch can deliver Jason the return he has craved from the outset (A.R. 1.535). She has yet to realise this. ‘No, would that he had escaped unharmed!’ The wish is in the past, her hero doomed and, sweetly, she prays to Hekate for his salvation, for his νόστος.

The closing betrays her – οὕνεκεν οὔ οἱ ἔγωγε κακῇ ἐπαγαίομαι ἄτῃ (470), ‘I at least take no joy in his terrible fate.’ An inner conflict between shame and desire is stirring. In the shade of Hekate’s temple, Persuasion will tip the balance.

ἡ μὲν ἄρ᾽ ὧς ἐόλητο νόον μελεδήμασι κούρη.

A.R. 3.471

So then was the girl disturbed at heart by love cares.

The girl κούρη and her reasoning νόος are being pushed apart by love cares μελεδήματα. The charm is working, Erato. She will sleep soon and dream of him (see Inside Medea’s Mind). She will speak with her sister, with her own tormented spirit. Eventually she will meet him at the temple of her goddess. And he will come like Achilles.

αὐτὰρ ὅ γ᾽ οὐ μετὰ δηρὸν ἐελδομένῃ ἐφαάνθη

ὑψόσ᾽ ἀναθρώσκων ἅ τε Σείριος Ὠκεανοῖο,

ὃς δή τοι καλὸς μὲν ἀρίζηλός τ᾽ ἐσιδέσθαι

ἀντέλλει, μήλοισι δ᾽ ἐν ἄσπετον ἧκεν ὀιζύν·

[960] ὧς ἄρα τῇ καλὸς μὲν ἐπήλυθεν εἰσοράασθαι

Αἰσονίδης, κάματον δὲ δυσίμερον ὦρσε φαανθείς.

A.R. 3.956-61

But soon he appeared to her longing eyes, striding on high like Sirius from the Ocean, which rises beautiful and bright to behold, but casts unspeakable grief on the flocks. So did Jason come to her, beautiful to behold, but by appearing he aroused lovesick distress (trans. Race).

References

Campbell, D. A. (1983) The Golden Lyre, London.

Campbell, M. (1983) Studies in Apollonius Rhodius, Hildesheim.

Crisp, P. (2003) ‘Conceptual Metaphors and its expressions’ in Cognitive Poetics in Practice, eds. J. Gavins and G. Steen, London: 99-114.

Feeny, D. C. (1991) The Gods in Epic, Oxford.

Hunter, R. L. (1989) Apollonius of Rhodes: Argonautica III, Cambridge.

Johnson, W. R. (1982) The Idea of Lyric, Berkeley.

Lowe, N. J. (2000) The Classical Plot and the Invention of Western Narrative, Cambridge.

Pavlock, B. (1990) Eros, Imitation, and the Epic Tradition, Cornell.

Stockwell, P. (2002) Cognitive Poetics: An Introduction, London.

Vivante, P. (1997) Homeric Rhythm: A Philosophical Study, Westport.

West, M. L. (1997) The East Face of Helicon, Oxford.

Research interests include intertextuality, indeterminacies, reader-experience and reader-manipulation.