Measuring Arrows in Time

Some thoughts on narrative duration making much use of arrows (and a handful of bullets). This post did run away with itself in its efforts to track the shots in text and time – duration reading for the durable reader!

Some thoughts on narrative duration making much use of arrows (and a handful of bullets). This post did run away with itself in its efforts to track the shots in text and time – duration reading for the durable reader!

αὐτὰρ ὁ σύλα πῶμα φαρέτρης, ἐκ δ᾽ ἕλετ᾽ ἰὸν

ἀβλῆτα πτερόεντα μελαινέων ἕρμ᾽ ὀδυνάων·

αἶψα δ᾽ ἐπὶ νευρῇ κατεκόσμει πικρὸν ὀϊστόν,

εὔχετο δ᾽ Ἀπόλλωνι Λυκηγενέϊ κλυτοτόξῳ

[120] ἀρνῶν πρωτογόνων ῥέξειν κλειτὴν ἑκατόμβην

οἴκαδε νοστήσας ἱερῆς εἰς ἄστυ Ζελείης.

ἕλκε δ᾽ ὁμοῦ γλυφίδας τε λαβὼν καὶ νεῦρα βόεια·

νευρὴν μὲν μαζῷ πέλασεν, τόξῳ δὲ σίδηρον.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ δὴ κυκλοτερὲς μέγα τόξον ἔτεινε,

[125] λίγξε βιός, νευρὴ δὲ μέγ᾽ ἴαχεν, ἆλτο δ᾽ ὀϊστὸς

ὀξυβελὴς καθ᾽ ὅμιλον ἐπιπτέσθαι μενεαίνων.

Il. 4.116-126

But he, removing the quiver’s lid, took from it an arrow – fresh, feathered, a ballast of black pains. And quickly on string he fitted the sharp arrow, and vowed to Apollo, the Lycian-born, the famous archer, to make splendid sacrifice of first-born lambs when he returned home to the town of holy Zeleia. And taking both notched shaft and ox-gut string, he drew them together; the string he brought near to his breast and to the bow brought near the arrow’s iron head. And so, when he stretched the great bow into a circle, the bow twanged and the string rang out and the arrow leapt – sharp-pointed, eager to fall among the crowd.

‘He’ is the Trojan warrior, Pandarus. He selects an arrow, draws his bow and fires: a one sentence summary of the action but the narrative of this sequence as we encounter it here spans eleven lines of hexameter verse. The expansion is due to additional information, to qualifications, to the zooming-in on details. We start with the container as our attention is drawn first to the quiver ‘and he took from it an arrow’.

The object selected ἰὸν appears at verse end but only emerges fully into view in the details which follow: ἀβλῆτα (‘unused, fresh’), πτερόεντα (‘winged, feathered’), μελαινέων ἕρμ᾽ ὀδυνάων (‘of black, the ballast/freight of pains’). There are no conjunctions and asyndeton increases speed – three qualities flashing one after the other. And yet each flash is longer (in syllables then words – in Text-Time) than the last. The image of the arrow is drawn and is drawn out across the span of the line. Two verses and we have our arrow – a special arrow. How special we do not know but details were given and Time was taken. The presentation suggests this isn’t any arrow.

Opening verse 118, the adverb αἶψα (‘quickly’) signals urgency in what follows but once notched, there is no release. Again a verse ends on the object: here ὀϊστόν qualified by the preceding adjective πικρόν (‘sharp, pointed, bitter’). The arrow’s negative potentials accumulate. There is no release because first the archer prays and makes his promise of sacrifice to a deity fit for the purpose; to Apollo, the Lycian-born, the famous archer. Now whilst I don’t wish to clutter analysis with extra text (just yet), two short extracts from earlier in the poem (from the Catalogue of Trojan allies in Book 2) help underline Apollo’s suitability.

οἳ δὲ Ζέλειαν ἔναιον ὑπαὶ πόδα νείατον Ἴδης

ἀφνειοὶ πίνοντες ὕδωρ μέλαν Αἰσήποιο

Τρῶες, τῶν αὖτ᾽ ἦρχε Λυκάονος ἀγλαὸς υἱὸς

Πάνδαρος, ᾧ καὶ τόξον Ἀπόλλων αὐτὸς ἔδωκεν.

Il. 2.824-27

The Zeleians lived below the lowest foot of Ida – a wealthy people, drinking the dark waters of the Aesepus, Trojans – and Lycaon’s famous son led them, Pandarus, to whom Apollo himself gave the bow.

Pandarus and his people are the Trojans’ kinsfolk. He has a special relationship with Apollo. The bow on which he notches this arrow is a gift from the god (perhaps, see below).

Σαρπηδὼν δ᾽ ἦρχεν Λυκίων καὶ Γλαῦκος ἀμύμων

τηλόθεν ἐκ Λυκίης, Ξάνθου ἄπο δινήεντος.

Il. 2.876-77

Sarpedon led the Lycians, he and splendid Glaucus, from faraway Lycia by the whirling Xanthus.

Apollo has strong links with the Lycians, these Trojan allies whose mention concludes the Catalogue and Book 2. He is the god a wounded Glaucus prays to for aid (Iliad 16.513f.), and the god who answers that prayer. The epithet is pointed – the god is on the side of Lycia, Troy and Pandarus.

The following epithet is likewise precisely aimed: at the god known for his skill with a bow and at a god whose archery has already been observed in the narrative, and on behalf of Troy. The god was introduced in the proem (1.9) when the narrator answered his own question ‘Who first caused Achilles and Agamemnon to quarrel?’ It was the son of Zeus and Leto.

That answer initiated the narrative itself for preliminary summarised exposition becomes scene when Apollo’s priest Chryses petitions Agamemnon for the release of his daughter (in direct speech, 1.12-21). Agamemnon refuses (1.22-32). Chryses prays to Apollo (in direct speech, 1.33-42) and Phoebus Apollo hears him (ὣς ἔφατ᾽ εὐχόμενος, τοῦ δ᾽ ἔκλυε Φοῖβος Ἀπόλλων, 1.43). The god hears him and the god acts. His arrows bring pestilence to the Greek camp. Just one more extract…

ἔκλαγξαν δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ὀϊστοὶ ἐπ᾽ ὤμων χωομένοιο,

αὐτοῦ κινηθέντος. ὃ δ᾽ ἤϊε νυκτὶ ἐοικώς.

ἕζετ᾽ ἔπειτ᾽ ἀπάνευθε νεῶν, μετὰ δ᾽ ἰὸν ἕηκε·

δεινὴ δὲ κλαγγὴ γένετ᾽ ἀργυρέοιο βιοῖο.

Il. 1.46-49

The arrows clattered on the shoulders of the angry god as he moved. And he came like night. He set himself far from the ships and let fly an arrow. And terrible was the twang of the silver bow.

We’ll leave Apollo twanging there for now though and return to Pandarus. We do not hear his prayer quoted in Direct Speech but read instead a summary of its contents; a summary which still occupies another two lines of verse reporting the promise of the archer looking beyond his successful shot to a future sacrifice on his return home from the war. Then he stretches.

We’ll leave Apollo twanging there for now though and return to Pandarus. We do not hear his prayer quoted in Direct Speech but read instead a summary of its contents; a summary which still occupies another two lines of verse reporting the promise of the archer looking beyond his successful shot to a future sacrifice on his return home from the war. Then he stretches.

We see the notch on the shaft fitted to the string, on the string made of ox-gut. We see the notched arrow pulling back against his breast. We see the tip of the arrow coming to meet the frame of the bow. We pull back and see the whole coming together in a circle. Detail is added to detail with each addition suspending the execution of the shot.

How many references to arrows and bows pepper verse endings? ἰόν (the arrow, 116), ὀϊστόν (the arrow, 118), κλυτοτόξῳ (the archer, 119), then following the prayer τόξῳ δὲ σίδηρον (to the bow the arrow-head, 123) and τόξον ἔτεινε (the bow pulled back, 124). Only then does the bow twang. Not once (λίγξε βιός) but twice (νευρὴ δὲ μέγ᾽ ἴαχεν). Three verbs carry the whole sequence, this time with polsyndeton – twang and sound and leaps the arrow! The string sings. The archer god is a musician too, both bow and lyre are his. The string sings and the arrow dances from it. ὀϊστόν again at verse-end and again, as when pulled from its quiver, not unaccompanied. Earlier it was preceded by the qualification πικρόν, now followed by the qualification ὀξυβελής. Fresh, feathered, pain-bearing, bitter, sharp and finally ‘sentient’ when μενεαίνων closes the extract. After eleven verses, the arrow is itself impatient, ‘eager’ to fall upon its target.

There was a point to the pacing of that reading. I want to talk about duration, also labelled rhythm; not the rhythm of form, not the six beating feet of the verse but the rhythm of that verse’s narrative. This is duration/rhythm as an aspect of Narrative Time (and with Frequency and Order it makes Time’s trinity) and an aspect dependent upon the tripartite (three is a magic number) narratological model fundamental to my reading approach: Text – Narrative – Story.

Now, Text-Time (TT) is absolute. TT here is eleven lines of hexameter verse and every word (sign) within them. TT is ‘measured by the yardage of physical signs from which the text is constructed, irrespective of the pace of sequence of their processing by the reader’ (Lowe 2002:36). Story-Time (ST) is also absolute. ST is measured in seconds, minutes and hours. Time operates in a Storyworld in the same manner as it does in our world. The clock ticks for Pandarus outside the walls of Troy just as it ticks for me when sat at my desk typing this sentence (and for you now reading – [tick-tock] – what I have typed in the past).

A measurement in Space and a measurement in Time could be used (and has been and is used) to calculate duration (and there are discussions in Bal (1997: 99f.) and Genette (1980: 87f.) for those interested in ratios of words per second). But, let’s look again at Pandarus, thinking about speed and about how action is being narrated. Picking out the bare sequence of events, what just happened? He picked an arrow, took aim and fired. What’s taking up the space in Text-Time?

A measurement in Space and a measurement in Time could be used (and has been and is used) to calculate duration (and there are discussions in Bal (1997: 99f.) and Genette (1980: 87f.) for those interested in ratios of words per second). But, let’s look again at Pandarus, thinking about speed and about how action is being narrated. Picking out the bare sequence of events, what just happened? He picked an arrow, took aim and fired. What’s taking up the space in Text-Time?

In my reading, I picked out various components. For example, there are the additional adjectives which describe physical properties of the arrow and the bow: fresh, feathered, iron-tipped, ox-gut string. There is information on its potential effect: ‘ballast of black pain’ looks forward. It anticipates the aftermath of impact by signposting something universal in all weapons (damage-ability). There is the reported speech narrated in past tense but prospective at the time of utterance. It also looks forward but beyond the imagined success of the shot to a future time when Pandarus returns home. There is the zooming-in on movements and relative positions: arrow to string, string to chest, arrow-head to bow. There is the stepping back to survey the whole made a circle. There is not one but three verbs conveying the moment of release. There is the emotional quality attributed to the arrow in flight when animated in that release, it leaps from the string and into life, and in life it desires its mark.

The point I am making by modified repetition (FREQUENCY) of earlier observations is that Time as presented in this narrative is slowed down. Pressed to label the tempo here, my response would be that this presentation (all elements taken together) is STRETCH: ‘A narrative speed or mode of DURATION faster than PAUSE but slower than SCENE, in which both narration and action progress but what is told transpires more rapidly than the telling’ (Herman 2009: 193). It is a tempo commonly found ‘in Homeric descriptions of woundings’ (Lowe 2000: 40). But before we all start mouthing STRETCH and nodding along contentedly, let’s give the system a shake.

He picked an arrow, took aim and fired.

If that was our narrative and not my extraction of an event sequence from the narrative, is there enough there for a reader to construct a mental picture? I think so. Based on reading-experience of all manner of narrative media (e.g. novels, comics, film) or on purely visual representations, we can create a mental sequence for an archer firing a bow. Two questions then. 1. Why classify the presentation at Iliad 4.116-26 as STRETCH and not SCENE? 2. What effects does the speed of the presentation have on the reader? The first question relates to how we classify, to fuzzy borders and tempi relative to presentation. The second relates to classification because, yes, I can label it STRETCH but to that labelling, ‘Okay, so what?’ is a perfectly valid reader’s response.

…even when heroes are acting rather than speaking their actions are usually described at a leisured [my italics] pace and hence scenically. For examples, Telemachus’ departure for Pylos is narrated in full [my italics] detail: the bringing of provisions on board, taking their seats, raising the mast, and pouring libations for the gods (Od. 2.414-433). As in most narratives, scenes alternate with summaries; thus the scene of Telemachus’ departure is capped by a summary: ‘all night long and into the dawn the ship ran on her journey’ (Od. 2.434).

Question one then. I cite the above passage because it’s relevant to the handling of Narrative Time in Homeric epic, because it concisely makes clear the most obvious alternations of duration in fictional narrative (between SCENE and SUMMARY), and because it enabled me to highlight some problems, such as the implication of ‘full detail’. Similar comment occurs in On Style, when Demetrius turns to a discussion of ‘Vividness’ (ἐνάργεια) of style and begins with Homer (Libro de Elocutione 4.209-11, translations by D.C. Innes, my italics).

Vividness derives in the first place from accurate detail and the fact that no circumstance is omitted or deleted…

His comment on the simile at Il. 21.257f.

It is vivid because all the details are included and nothing is left out.

And his comment on the chariot-race at Il. 23.379f.

The whole passage is vivid because it includes all the race’s usual and unusual features.

Full details, accurate details, all the details… Details yes, more than in SUMMARY yes (details do indicate SCENE not SUMMARY), but all the details? No. ‘Full detail’ is a narrative impossibility – the yardage of text would run and run. Narrative, however ‘full’ it appears, it always a selective presentation. If (returning to de Jong’s example) Telemachus’ departure was narrated in full detail, I should be able to extrapolate instructions (practical or otherwise) for how to launch Bronze Age sailing vessels or the proper ritual practice for offering libations to Olympians (order of steps, words to say, instruments to use and so on). That’s unfair on de Jong who is drawing attention effectively to the most common alternation in duration (and I do no better in the following comments) but the opportunity was there to reiterate the selectivity of narrative (and I took it).

But what about ‘leisured’? To me, ‘leisured’ suggests ‘slower than normal’ and if SCENE is leisured what then is STRETCH? More leisured? Bal, taking a expansive view of SCENE that squeezes STRETCH (‘slow-down’ in her terminology), finds this tempo rare in any case: ‘Difficult if not impossible as it is already to achieve perfect synchrony in a scene, because the presentation is too slow, imagine slowing down even more’ (1997: 108). My scene is smaller and I’m prepared to imagine.

What I understand by ‘leisured pace’, or what else I choose to take it to mean, is comment on the Odyssey’s style of narration, – the sort of comments, now creating some imaginary paratext, we might find on a ‘back-cover’ of Homer.

Every passage in him that one touches is exquisitely elaborated in both the austere and smooth manners.

– Dionysius of Halicarnassus

He combines luxuriance and concision, charm and gravity; he is a miracle of copiousness as well as brevity, and he is outstanding in the qualities of an orator as well as a poet.

– Quintilian

Each word leans forward, preparing the ground for the next one. Words melt into phrase, phrases into sentence, sentence into verse; and meaning arises from the enveloping moment.

– Paulo Vivante

Those three samples (De compositione uerborum 24 trans. Russell, Institutio Oratoria 10.46 trans. Winterbottom, and Homeric Rhythm 1997: 35) contain comments which for the most part relate to the Homeric style of presentation (as with Demetrius’ comments above); to which everything from particles and conjunctions to epithets, similes, repetitions and descriptions (for example) might contribute. And to which we can add other integral components of communication such as sound (these deviations might become too stretched, but see e.g. the chapter on aural interaction in Michael Silk’s Interaction in Poetic Imagery).

When I first mentioned duration/rhythm I made a distinction between rhythms (between narrative tempi and the short and long syllable combinations that make up the hexameter ‘beat’) that in practice is not so straightforward – hence de Jong’s ‘leisured pace’. Dionysius, for example, takes to counting syllables in an analysis of the narrative of Sisyphus rolling his stone in the Underworld (Odyssey 11.593ff.). I quote from the ‘down-hill’ section to give a sample of his method.

αὖτις | ἔπειτα | πέδονδε | κυλίνδετο λᾶας ἀναιδής.

Od. 11.598

Then back earthwards again rolled the pitiless stone.

Does not the word-arrangement roll downhill with the weight of the rock – or rather, the speed of the narrative [τὸ τῆς ἀπαγγελίας τάχος] overtake the momentum of the stone? I believe it does. Once again – why? The answer is worth noticing. The line which represents the downward movement of the rock contains no monosyllabic, and only two disyllabic, words. This, in the first place, accelerates rather than extends the intervals. Further, of the seventeen syllables in the line, ten are short and only seven long and those are not perfect ones: the expression is therefore inevitably contracted and compressed under the influence of the shortness of the syllables. Again, no word has any appreciable separation from the next: no vowel is in juxtaposition with another vowel, no semivowel or consonant with semivowel – and these are the features which roughen or break up word structure.

Those readers suitably tantalised to investigate further will find that he has more to say on that verse, though as Russell (1995: 54) has noted, he did fail to spot those opening three trochaic caesurae (for shame, Dionysius! I’ve marked them out). Apangelia is the noun Russell translates here as ‘narrative’. Other translations include ‘report’ and ‘recital’ and it’s used by Aristotle for the poet speaking ‘himself’ (in simple diēgēsis, so Halliwell 1998: 128 n.34 citing 48a, 22, 60a). That is not strictly the case here as Odysseus is the intradiegetic (character) narrator (in mitigation, he did begin speaking to his Phaeacian audience back at Odyssey 9.2 and hasn’t taken a break) but the idea of recital takes us to ‘Longinus’ and the synthesis of words and sound in the performance of poetry.

The combination and variety of its sounds convey the speaker’s emotions to the minds of those around him and make the hearers share them. It fits his great thoughts into a coherent structure by the way in which it builds up patterns of words. Shall we not then believe that by all these methods it bewitches us and elevates to grandeur, dignity, and sublimity both every thought which comes within its compass and ourselves as well, holding as it does complete domination over our minds? It is absurd to question facts so generally agreed. Experience is proof enough.

Or, as the Homeric narrator comments when Odysseus does conclude his character narration of his own Wanderings.

ὣς ἔφαθ᾽, οἱ δ᾽ ἄρα πάντες ἀκὴν ἐγένοντο σιωπῇ,

κηληθμῷ δ᾽ ἔσχοντο κατὰ μέγαρα σκιόεντα.

Od. 13.1-2

So he spoke, and they all stayed still and silent, spellbound beneath the shadowy halls.

So many elements, all coming together, create the ‘leisured’ texture of Homeric narrative as a whole, through engagement with which as an audience we become immersed (bewitched, spellbound) in the Storyworld. My ‘he picked an arrow, took aim and fired’ is a time-ordered sequence of events. Is it a narrative? We could add more.

In the tenth year of the war, the Greeks and Trojans agreed to a ceasefire. But during the negotiations, Pandarus saw an opportunity to end the war there and then. As the leaders of the opposing forces stood discussing terms, Pandarus drew his bow. He picked an arrow, took aim and fired. However, he missed his shot and the fighting broke out again. For the next four days it was especially fierce.

It’s not a very good narrative (making an aesthetic judgement, it is lacking in ‘narrativity’) and I suspect unlikely to immerse anyone, but it is a narrative. Is it SUMMARY? Is it SCENE framed by SUMMARY? Mieke Bal talks about the fuzzy borders between the five tempi of narrative rhythm. I’ll repeat the five using Herman’s definition: ‘in order of increasing speed, these are PAUSE, STRETCH, SCENE, SUMMARY, and ELLIPSIS.’

Now, an ellipsis is a gap. It is an absence in the narrative. ‘We know that something must have happened, and sometimes we know approximately where, but usually it is difficult to indicate the exact location’ (Bal 1997: 103). Sometimes though we get an indication.

a When I was back in New York after two years.

We know exactly how much time has been left out. It is even clearer when an ellipsis is mentioned in a separate sentence.

b Two years passed.

In fact, this is no longer an ellipsis, but could be called a minimal summary, or rather, a summary with maximum speed: two years in one sentence.

Such a pseudo-ellipsis, or mini-summary, can be expanded with a brief specification concerning its contents:

c Two years of bitter poverty passed.

The pseudo-ellipsis is beginning to look more and more like a summary.

Fuzzy borders. Now in my Pandarus narrative, the opening sentence looks like summary and the last sentence looks like (minimal) summary. What about when he sees his moment and acts? Is he too fast for it to be a scene, for it to be considered norm tempo? What if I added a sentence of direct speech? – ‘Now’s my chance to make a scene,’ said Pandarus. What if the narrative continued in the same stripped-down manner of presentation, of summarised passages of time alternating with short strings of event sequences? Would those event sequences, impossibly bare in comparison with Homeric narrative, nevertheless be a scenic norm for my hypothetical narrative? No, you say, because Narrative Time is measured against Story Time which is Real Time and NT is roughly equal to ST so my Pandarus is moving too fast. Probably.

I suppose what’s bothering me is the question ‘When we read a text, engage with its narrative, immerse ourselves in the Storyworld, how aware are we of the clock? How accurate is our clock? How accurate does it need to be?’ Okay that was three questions. I’d say in the case of Homer’s Pandarus taking his shot, we are aware (without needing to go and find a bow) that NT is slower than ST (= RT). Thus here NT > ST therefore NT = STRETCH. But what about when it’s not so obvious? And SCENE, our norm tempo, is only roughly equivalent to ST even when quoting dialogue.

All that we can affirm of such a narrative (or dramatic) section is that it reports everything that was said, either really or fictively, without adding anything to it; but it does not restore the speed with which those words were pronounced or the possible dead spaces in the conversation.

Most scenes are full of retroversions, anticipations, non-narrative fragments such as general observations, or atemporal sections such as descriptions.

Do we strip the non-linear and non-narrative ‘padding’ when we read? Do we look for cues as to how quickly a character might speak? And what is considered slower than or faster than normal (SCENE) in one presentation might be in another presentation considered normal (SCENE). Here’s an extract from an analysis of Time in Pindaric Narrative.

Summaries are also of importance in a second recurrent type of Pindaric narrative. Here the Pindaric narrator chooses to focus on a short scene within a larger myth. The chosen scene is narrated in some detail (i.e. slowly [my italics]), sometimes involving fairly extensive speeches, whilst the bulk of the entire story is either narrated in summary fashion or omitted altogether… The result is a striking difference in narrative speed between scene and summary.

Again deceleration appearing in a definition of SCENE. That the alternations in tempi are striking I do not doubt, but there is no ST in the analysis and this SCENE is slow. Aren’t speeches an indicator of roughly average time? What the narrative here seems to be being measured against is itself, and not against a clock. If Pindaric narrative was set beside Homeric narrative, would it still be considered ‘slow’? At a push, it would be ‘average’. Returning to the clock and our awareness of it, my suspicion is that we read (as this passage seems to me to be doing) alternations of tempi relatively within a narrative and between narratives. In reading we establish a scenic norm for that specific narrative presentation (with all its padding included) and read against it. SCENE = (NT≈ST) but also SCENE = (NT≈(A)NT). And I say this aware that I am falling back on the ‘Longinus’ approach – ἀποχρῶσα γὰρ ἡ πεῖρα πίστις. More arrows are required. And bullets.

When Chryses prayed to Apollo, the god heard him and his response was scenic. Down from Olympus he came with his bow and his quiver. And as we’ve read in Il. 1.46-49 above, he found a position, settled himself and began to shoot. After the first twang, arrow after plague-bearing arrow flies from the silver bow (Arrow-Time = Legolas? Arrow-Time < Crow?).

When Chryses prayed to Apollo, the god heard him and his response was scenic. Down from Olympus he came with his bow and his quiver. And as we’ve read in Il. 1.46-49 above, he found a position, settled himself and began to shoot. After the first twang, arrow after plague-bearing arrow flies from the silver bow (Arrow-Time = Legolas? Arrow-Time < Crow?).

οὐρῆας μὲν πρῶτον ἐπῴχετο καὶ κύνας ἀργούς,

αὐτὰρ ἔπειτ᾽ αὐτοῖσι βέλος ἐχεπευκὲς ἐφιεὶς

βάλλ᾽· αἰεὶ δὲ πυραὶ νεκύων καίοντο θαμειαί.

Il. 1.50-2

The mules first he hit, and the swift dogs; but then he launched his sharp arrows against the men and struck them – and always the fires of the dead burned thick.

The body-count mounts and scene shifts into summary marked not immediately by a temporal clause but through the image of ever-burning pyres – fires in the night signal the passing of lives and time in the aftermath of a god’s onslaught. As Quintilian put it on our back-cover, ‘he is a miracle of copiousness as well as brevity’. The Homeric narrator knows how to play (minimal) summary against scene; most remarkably (and tangentially) when Zeus placed the fates of Achilles and Hector on the scales (Il. 22.208f.). Hector’s fate sank down to Hades ‘and Phoebus Apollo left him’ (λίπεν δέ ἑ Φοῖβος Ἀπόλλων, 22.213).

But we shall leave Phoebus Apollo in turn and, shifting east from Troy and forwards in Real-Time but backwards in Story-Time, review another archer god in scenic action in Colchis.

ὦκα δ᾽ ὑπὸ φλιὴν προδόμῳ ἔνι τόξα τανύσσας

ἰοδόκης ἀβλῆτα πολύστονον ἐξέλετ᾽ ἰόν.

[280] ἐκ δ᾽ ὅγε καρπαλίμοισι λαθὼν ποσὶν οὐδὸν ἄμειψεν

ὀξέα δενδίλλων· αὐτῷ ὑπὸ βαιὸς ἐλυσθεὶς

Αἰσονίδῃ γλυφίδας μέσσῃ ἐνικάτθετο νευρῇ,

ἰθὺς δ᾽ ἀμφοτέρῃσι διασχόμενος παλάμῃσιν

ἧκ᾽ ἐπὶ Μηδείῃ· τὴν δ᾽ ἀμφασίη λάβε θυμόν.

A.R. 3.278-284

And quickly, at the base of the doorpost in the vestibule, Eros strung his bow and took an arrow – fresh, mournful – from his quiver. From there, with swift steps he crossed the threshold unobserved, looking keenly around. Then crouching down small by Jason’s legs, he placed the arrow’s notches in the centre of the bowstring, and pulling it straight apart with both hands, he shot at Medea; and speechless amazement seized her heart.

Positioning, aiming and the hit done in seven hexameters. Even a superficial glance at Text-Time indicates that this is a tighter presentation than the Pandarus narrative (whose arrow is yet to find its mark after eleven hexameters). There are still details e.g. two adjectives qualify the arrow and Eros’ actions are narrated sequentially. He selects an arrow, he sneaks into the hall searching out his target then finds his position. No reported prayer extends the duration – the god has no need of prayers (and readers of the Metamorphoses might consider this god the better archer in any case). There is not the zoom-in and zoom-out on the action when Eros takes aim, but simply a notch and pull back. There is not the abundance of adjectives nor the varied repetition and references to arrows and bows that stretch the Pandarus narrative.

Yet there is more than enough for a reader to construct an image. The details are scenic right up until the shot. And then – a gap. Hunter comments: ‘The monosyllabic verb after a lengthy presentation (278-83) and the central punctuation ‘dividing’ two references to Medea mark the speed and stunning effect of the shot’ (1989: 129). The target is sighted, named, then shot – no twang, no bang, faster than sound and sight this arrow flies: ‘and speechless amazement seized her heart.’ The arrow’s trajectory and impact is in the ellipsis; it is presented in absence, in the infinity of no-time.

And what about those two adjectives qualifying the noun? The alert reader will spot that one has been used earlier. Pandarus’ arrow was likewise ἀβλῆτα (‘unused, fresh’) and there is a literary joke in play here. Hunter has noted that Pandarus’ shot was the model for Eros’ own and further that πολύστονον perhaps glossed a ‘difficult’ μελαινέων ἕρμ᾽ ὀδυνάων (1989: 129). What about ‘unused’? In their context, both arrows are fresh. But we have seen this arrow before – in the model. Reading intertextually, this arrow is not unused but being reused and ἀβλῆτα is signalling its actual lack of uniqueness, its connection with its literary past. And as this narrative points to its Homeric model so its treatment also highlights its differences – not STRETCH but SCENE and ELLIPSIS; an invisible arrow fired by a god (properties of instrument and agent which recall the plague-bearing arrows of Apollo – and Medea’s ignited love will be presented imminently as a sickness (3.289)).

The temptation to press on into the scenic narration of this arrow’s effect on Medea (and the lyric ‘infection’ of epic it brings) was strong but having noted the differences in DURATION between the two presentations – STRETCH vs SCENE containing ELLIPSIS – we should switch targets, reveal who Pandarus’ arrow is eagerly seeking and attempt to address ‘So what?’

οὐδὲ σέθεν Μενέλαε θεοὶ μάκαρες λελάθοντο

ἀθάνατοι, πρώτη δὲ Διὸς θυγάτηρ ἀγελείη,

ἥ τοι πρόσθε στᾶσα βέλος ἐχεπευκὲς ἄμυνεν.

[130] ἣ δὲ τόσον μὲν ἔεργεν ἀπὸ χροὸς ὡς ὅτε μήτηρ

παιδὸς ἐέργῃ μυῖαν ὅθ᾽ ἡδέϊ λέξεται ὕπνῳ,

αὐτὴ δ᾽ αὖτ᾽ ἴθυνεν ὅθι ζωστῆρος ὀχῆες

χρύσειοι σύνεχον καὶ διπλόος ἤντετο θώρηξ.

Il. 4.127-133

And you, Menelaus, the blessed gods, the deathless ones, did not forget; and first among them Zeus’ daughter, the ravager, who stood in front of you and defended the sharp arrow. She kept it just far enough from the skin, like when a mother keeps a fly from her child, as he lies in a sweet sleep; and she deflected it to where the belt’s golden buckles joined and the corselet made a double layer.

He missed. Was he ever likely to make a ‘kill shot’ on Menelaus, husband of Helen and brother of Agamemnon? No. He was set up to fail and set up to fail by Athena. I have been disingenuous in omitting (and neglecting to offer any summary of) the verses prior to the arrow selection. I wanted to focus on the ‘Load and Shoot’, and to keep the reader in suspense, a suspense achieved here by the stretching out of the explication but in the Iliad by the stretching out of the presentation.

He missed. Was he ever likely to make a ‘kill shot’ on Menelaus, husband of Helen and brother of Agamemnon? No. He was set up to fail and set up to fail by Athena. I have been disingenuous in omitting (and neglecting to offer any summary of) the verses prior to the arrow selection. I wanted to focus on the ‘Load and Shoot’, and to keep the reader in suspense, a suspense achieved here by the stretching out of the explication but in the Iliad by the stretching out of the presentation.

A disguised Athena came to Pandarus and persuaded him to take the shot (Il. 4.86f. in SCENE). Our STRETCH began farther back than where we first viewed the text. It began in a retroversion after Pandarus took up his bow: the description of its material became a backstory of the goat he hunted and killed – how he killed it, the size of its horns, and how its horns were made into the bow (Il. 4.105-111, and somewhat at odds with the earlier reference to Apollo gifting him the bow!). There followed an account of how his comrades protected him whilst he prepared the shot. His prayer between selection of arrow and stretching the bow is a reported repetition of Athena’s instructions to him in direct speech at Il. 4.101-3. From taking the bow (4.105) to Athena’s scenic deflection (4.129) is a thirty verse STRETCH.

I say SCENIC deflection because it’s faster than what precedes and faster than what follows. Another seven lines of verse must be negotiated on the arrow’s traversal before flesh is hit and a non-mortal wound inflicted. This is another stretch as de Jong (2007: 32) has observed ‘presented in great length and at great detail.’

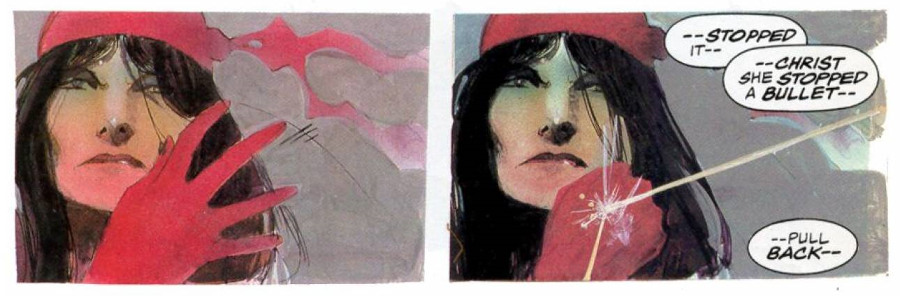

In comparison with what surrounds it, Athena’s action is both effortless and fast, but still action. In terms of duration, this is SCENE flanked by STRETCH rather than the common alternation of SUMMARY and SCENE. Its tempo is faster than e.g. the tempo of the triptych of panels painted by Bill Sienkiewicz (taken from the 1986-7 limited series Elektra: Assassin by Miller and Sienkiewicz). That first panel captures the bullet in flight, then in the second a faint motion line is used to convey the movement of Elektra’s hand into the bullet’s path. In the final panel, the image is repeated but with darker colours and thicker splashes of paint giving a more menacing impression whilst her open hand is formed into a fist. Our view is that of the shooters. We stare straight at her whilst bubbles of text without a point of origin communicate multiple shocked reactions of assailants/witnesses – it’s a STRETCH.

Elektra’s extraordinary speed is conveyed via this slow-motion breakdown over three panels. Athena’s extraordinary speed is conveyed via her speed in comparison with what surrounds it. In film, in which the rate of frames per second dictates the norm tempo of duration, that frame rate can be sped up (as in the Crow link above) or stretched. In The Matrix, the superhuman speed of Neo (as he starts to believe) is conveyed in ‘bullet-time’. In these alternative examples, however, the point is the speed, for what we are being invited to marvel at is a character’s ability to move faster than what is humanly possible. The Athena presentation is more complex.

The goddess (herself following the request of Zeus following the request of Hera) has orchestrated a sequence of events to break the truce and for the Trojans to be the ones who break it. For the narrative to proceed, the shot must be taken. It will be taken but only after a considerable stretch in which the reader can ponder its implications, perhaps even consider (without ever really believing) that Pandarus’ prayer will be granted. It is a pivotal moment and made more so by the extended duration. This creates suspense.

We watch every movement as the moment of the arrow’s release crawls closer. We grow tense for a resolution expected or otherwise and in our tension invest the presentation with further significance. Everything rides on the shot. Duckworth, discussing foreshadowing, has observed how following this violation Agamemnon’s declaration ‘that the day will come when Troy shall fall and the Trojans shall perish as a result of their perjury’ (1966: 30, citing 4.158-68) confirms the reader’s certainty of the outcome. That certainty I believe is underscored by the presentation, by this manipulation of duration.

And Athena’s role? She made Pandarus the fall-guy and when the arrow flew she swatted it aside in an instant. Menelaus had to bleed but he was never going to die. I’ll let the reader read into that what they will regarding the roles played by men and gods in epic. More remains to be said on the comparisons between what follows in Apollonius’ narrative when compared with the model. And the aside on the Metamorphoses suggests another episode for fruitful correspondence but this post has accrued enough yardage for now.

“She was a great huntress, and daily she used to hunt, and ever she bare her bow with her.” Illustration by William Russell Flint in Sir Thomas Malory’s ‘Le Morte d’Arthur’, 1910-11.

References

Bal, M. [1980] (1997) Narratology: introduction to the theory of narrative, 2nd edn., Toronto.

Duckworth, G. E. (1966) Foreshadowing and Suspense in the Epics of Homer, Apollonius and Vergil, New York.

Genette, G. [1972] (1980) Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, trans. J. E. Lewin, Ithaca, New York.

Halliwell, S. [1986] (1998) Aristotle’s Poetics, 2nd edn., London.

Herman, D. (2009) Basic Elements of Narrative, Oxford.

Hunter, R. L. (1989) Apollonius of Rhodes: Argonautica Book III, Cambridge.

de Jong, I. J. F. (2007) ‘Homer’ in I. J. F. de Jong and R. Nünlist, eds., Time in Ancient Greek Literature, Leiden, 17-37.

Lowe, N. J. (2000) The Classical Plot and the Invention of Western Narrative, Cambridge.

Nünlist, R. (2007) ‘Pindar and Bacchylides’ in I. J. F. de Jong and R. Nünlist, eds., Time in Ancient Greek Literature, Leiden, 233-251.

Russell, D. A. & Winterbottom M. [1972] (1978) Ancient Literary Criticism: The Principal Texts in New Translations, 2nd edn., Oxford.