How to read dreams: narratological and stylistic analyses of Metamorphoses 4.27

Apuleius’ Metamorphoses, better known as The Golden Ass, is a Latin novel containing the misadventures of one Lucius, a man who’s transformed into an ass for a time. The primary narrative is delivered by a now-restored Lucius (the narrating ‘I’) looking back on his earlier asinine self (the experiencing ‘I’). The first time I encountered this text was as an undergraduate wrangling with the Latin of its most famous episode, the embedded tale now known as the ‘Cupid and Psyche’; the second time was as seminar leader on my then PhD supervisor’s nascent narratology module for which he had selected The Golden Ass as a set-text.

Lucius’ life in Books 1-10 is an open-ended anthology of episodes, serially strung together by the single commonplace denominator of the protagonist’s name. Lucius shares each episode with the reader as a separate atom of narrative, not as a further stage in the construction of a meaningful whole. As Lucius says, comparing the insight (prudentia) achieved by Odysseus as a result of his adventures, “I confess myself gratefully grateful to my ass for rendering me, while hidden under its hide and vexed by various fortunes, well, less astute, I admit, but widely informed [Metamorphoses 9.13].”

Indeed the narratological analysis here is a reworking (following a rereading) of a part of what I’d created back in 2016 as a sample commentary answer for the students taking the module. This time, however, it is rooted in the original Latin accompanied by my literal English translation rather than P. G. Walsh’s more fluid rendering of the text. The second and more involved update involves my rudimentary application of certain approaches drawn from modern stylistics to the extract. The impetus to attempt this was set in motion by my attendance at last year’s Poetics and Linguistics Association conference and some of the papers I heard that sunny July in Liverpool which in the current climate already feels a time and place remote. Should subsequent content and references not make it clear, I’m especially indebted to papers given at the conference by Patricia Canning and Louise Nuttall (though for all flaws in the application here I claim full credit).

So much for the background to my occasion for telling.

We are not looking at the entirety of 4.27 here, only at the conclusion of a character speech in which a young woman relates her dream, both because dream narratives retain their especial interest for me (see e.g. A.R. 3.616-632: Inside Medea’s Mind) and because this seems a manageable amount of text for my preliminary stylistic analysis.

Briefly, however, we can situate the extract in its own performative context. There are three speaking voices in 4.27: two character-narrators and Lucius the primary narrator framing the character speeches with his own comments. The location is a bandits’ den and the first speaker is a young woman that the bandits have kidnapped. Her addressee is an old woman who works for the bandits and who will go on to narrate the ‘Cupid and Psyche’ after making an initial response on the nature of dreams. Also present and listening are Lucius-as-Ass in the storyworld and we readers outside of it.

“I could tell you my adventures — beginning from this morning,” said Alice a little timidly, “but it’s no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then.”

“Explain all that,” said the Mock Turtle.

A First Reading of the Dream

‘Sed ecce saevissimo somnio mihi nunc etiam redintegratur, immo vero cumulatur infortunium meum. nam visa sum mihi de domo, de thalamo, de cubiculo, de toro denique ipso violenter extracta per solitudines avias infortunatissimi mariti nomen invocare, eumque, ut primum meis amplexibus viduatus est, adhuc unguentis madidum, coronis floridum consequi vestigio me pedibus fugientem alienis: utque clamore percito formosae raptum uxoris conquerens populi testatur auxilium, quidam de latronibus importunae persecutionis indignatione permotus saxo grandi pro pedibus arrepto misellum iuvenem maritum meum percussum interemit: talis aspectus atrocitate perterrita somno funesto pavens excussa sum.’

Adjectives and Adverbs emboldened.

Verb forms whether finite verbs, infinitives or participles underlined.

Instances of embedded focalisation italicised.

‘But look just now my misfortune is renewed for me by a most cruel dream, no in fact it’s overloading. For I seemed to myself dragged violently from my home, my apartment, my bedroom, finally from my very bed and through trackless wastelands I called my unfortunate husband’s name. And he, as soon as he was deprived of my embraces, still drenched with perfume, flowering with garlands, followed me on the trail fleeing on feet not my own. And when with an excited shout, lamenting the kidnap of his lovely wife, he calls for the people’s help, one of the bandits, stirred up with outrage of the troublesome pursuit, struck with a big rock snatched up by his feet and killed my poor boy, my husband. Terrified by the atrocity of such a spectacle, I woke shaking from a deadly sleep.’

This is the conclusion to her speech. Prior to this the girl has related the circumstances of her actual kidnapping, of which the dream is a distorted representation. Following an initial header summary which evaluates the dream as ‘most terrible’ she expands into a scenic treatment much enlivened with evaluative details.

The difference between events and their representation is the difference between story (the event or sequence of events) and narrative discourse (how the story is conveyed). The distinction is immensely important.

If we were to try and relay her dream story, stripped of evaluation, to a third party, we might try the following: The woman was taken from her house. She called for her husband as she was taken. He followed, raised the alarm and called for help. A bandit killed her husband with a stone. She woke up.

There are no alterations with the linear flow of Time in the narrative discourse as presented by the young woman but there is a marked amount of added qualifications and heavy usage of emotionally charged vocabulary.

‘But look here,’ she begins, popping her addressees’ attention back to her here and now after her flashback exposition of her kidnapping (on deictic pops and pushes, see Adjusting the dynamics of narrative interest with additional references ibid.). In the Latin word-order, somnium ‘the dream’ which is the agent of her troubles comes early in the sentence with the words then accumulating ahead of the abstract recipient infortunium ‘the misfortune’ she claims as her own. And ahead of the dream comes the attributive superlative adjective saevissimus, the dream is not just bad but cruel, not just cruel but most cruel – highly graded then both lexically and grammatically.

The first two clauses construe emotions – I hate cockroaches more than rats and I don’t like cockroaches either. The verbs serving as Process are lexically gradable; they form points on a scale (detest, loathe – hate – dislike – like – love), expressing degrees of affection. The first clause is also graded grammatically, by a circumstance of degree – more than rats. This property of lexical and grammatical gradability is typical of ‘mental’ clauses construing emotions.

So then the young woman introduces her dream narration with her assessment of its contents, and in doing so provides a guide for our assessment as well as a teaser of what we might expect. The citation on gradability is taken from the fourth edition of Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar to which I was led via Dr Canning’s recommended post-PALA stylistic reading for the Classicist. One of the elements of dream-narratives which interests me is their presentation of agency e.g. reflections on the agency of the dreaming girl enactor in Inside Medea’s Mind. In Hallidayan systemic-functional linguistics (SFL), agency is one grammatical feature of the transitivity model which as a system is located within the experiential metafunction where it ‘has a markedly wider compass than its traditional grammatical definition as a verb that takes a direct object’ (Simpson & Canning 2014: 281).

Mapping the Transitivity Processes

One of the goals of Simpson & Canning 2014 is the development of a ‘transitivity-plus’ model ‘to account for the non-happenings, the imagined happenings and, for that matter, the imagined non-happenings in literature’ (281), a topic of great interest to this reader occupied with narrative gaps but also a topic for another post and time. For now I’m primarily interested in Simpson and Canning’s explication of the six key processes which make up the transitivity model and the preliminary part of their article.

- Material Processes are processes of ‘doing’ with two participants: the Actor ‘the doer’ and the Goal ‘the person or thing affected by the process.’ E.g. ‘the bandit killed the husband.’ If the process is intransitive, there is no Goal e.g. ‘the husband fell.’

- Mental Processes are processes of ‘sensing’ and ‘thinking’ with a Senser and a Phenomenon. E.g. ‘the bride (Senser) loved her groom (Phenomenon).’

- Behavioural Processes contain only one participant, the Behaver, and are either physiological processes e.g. ‘the young woman was shaking’ or states of consciousness ‘the young woman cried.’

- Verbalisation Processes have participant roles of Sayer, Receiver and Verbiage ‘which, without any implied derogatory sense, subsumes that which gets said through the process’ (Simpson & Canning 2014: 284). E.g. ‘The girl told the old woman her dream.’

- Existential Processes are processes of ‘existing’ featuring an Existent as the only participant role e.g. ‘There was an old woman.’

- Relational Processes are processes of ‘being’ which establish a relationship between a Carrier and an Attribute, which could be e.g. intensive (x is y), possessive (x has y) or circumstantial (x is at/on/with y). E.g. ‘The bride was young. She had a dream. The dream was about her groom.’

Now that is my adapted and simplified version of their account of Halliday 1994 (a recommended second edition of Introduction to Functional Grammar), an account limited ‘only to the most core terms, categories and criteria that make for a hands-on stylistic tool-kit’ (Simpson & Canning 2014: 282). Look again at the first sentence of our text.

Sed ecce saevissimo somnio mihi nunc etiam redintegratur, immo vero cumulatur infortunium meum.

Following an opening adversative conjunction, first spatial (ecce) and then temporal (nunc etiam) deictics preceding that present tense verb redintegratur ‘is renewed’ recenter her addressee on her here and now in the bandits’ cave, before the adverbial immo vero signposts a corrective ahead of the second present tense verb ‘is overloaded’. The dream she’s just had hasn’t just reminded her of her trouble but made it worse. And my summary has just recast her introductory statement to contain operative transitive processes: Dream [Actor] is refreshing/is overloading [Material processes] misfortune [Goal]. Simpson & Canning’s case study, a passage of Joseph Conrad’s novel Chance, tackles complexities of style not evident in our text such as prominent circumstantial elements within the processes and the elevated presence of meronymic agency. On the other hand what was absent in their text but markedly present in ours are receptive transitive processes (passive formulations): Misfortune [Goal] is being renewed/overloaded [Material processes] by Dream [Actor].

Transitivity probes the idea of ‘style as choice’ in that any particular textual pattern is only one from a pool of possible textual configurations. Transitivity therefore is a textual strategy that offers writers a systematic (if largely unconscious) choice about how they represent experientially the happenings of the physical or abstract world. What is of particular interest in stylistic analysis is why one type of structure should be preferred to another, how such preferences are motivated creatively, and what impact these patterns have on how the texts are experienced and interpreted.

Ahead of narrating the dream, the young woman gives it agency; she signals from the outset that the dream is cause of her condition exerting recognisable effects. Actions and events within the dream are presented in her speech following an explanatory conjunction nam ‘for’ and a passive verb of perception visa sum mihi ‘I seemed/appeared to me … ’. As she shifts back in time and projects (pushes us down) into her dream, the lack of agency remains, accompanied by a feeling of disembodiment projected by the experiencer’s phrasing – ‘I to me’.

Mapped as a mental process, the speaker here (the kidnapped young woman) is the Senser and the Phenomenon are the fact(s) which follow i.e. calling the name of husband, husband following her tracks. Within the dream itself there is only one other mental process (Phenomenon) that I (Senser) could discern (modulated Process), which is the bandit’s emotional response to a nuisance pursuit: the bandit (Senser) is stirred up (Process) with outrage at the troublesome pursuit (Phenomenon) ~ the troublesome pursuit outraged the bandit. The remaining processes occurring within the dream are either material or verbalisations.

Material Processes

| Process Type | ACTOR | PROCESS | GOAL | CIRCUMSTANCES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material (R) | by a dream (adjunct) | is renewed | misfortune | just now |

| Material (R) | by a dream (adjunct) | is overloaded | misfortune | |

| Material (R) | X | having been dragged | bride | from various locations |

| Material (R) | X | having been deprived | husband | of her embraces |

| Material (O) | husband | followed | bride | as she fled |

| Material (R) | by a rock (adjunct) | having been struck | husband | |

| Material (O) | bandit | killed | husband |

Simply in terms of the numbers, Material processes come out on top which is unsurprising as ‘doing’ processes are prototypical of narrative action, be that in a storyworld’s reality or a character’s narrated dream-world within that reality. The modern (English-speaking) reader, however, might be struck by the number of recipients having been dragged, stirred up, and struck. The caveat here is that without a past active participle (other than for deponent verbs) these passive constructions are commonplace in Latin and thus not necessarily a marker of stylistic deviancy (on which see e.g. Stockwell 2002: 61), so that the passive presence in my literal translation might appear more exaggerated than the original text would to a Latin reader and thus the translation increases the danger of ‘interpretative positivism’ (on which see further Simpson 1993).

Choosing a patient as the subject (such as in a passive), is a marked expression that requires some special explanatory motivation: defamiliarisation, or evading active responsibility, or encoding secrecy, for example.

Verbalisation Processes

With that in mind, the only process in the dream in which the young woman does evince agency is my first identified Verbalisation: through trackless wastelands [Circumstance] I called [Sayer] my unfortunate husband’s [Receiver] name [Verbiage]. In my mental re-enactment, the abductee is yelling ‘Bob! Bob!’ [insert preferential name of husband, which on a hindsight reading, once we discover his name, we can recast as ‘Tlepolemus, Tlepolemus!’] into a rushing by desert landscape in the hope he remains in earshot/is in pursuit.

| Process Type | SAYER | VERBIAGE | RECEIVER | CIRCUMSTANCES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbalisation | bride | name of husband | husband (intended) | through wasteland |

| Verbalisation | husband | kidnapping of wife | people (implied) | |

| Verbalisation | husband | help | people (implied) |

There is a projected anticipation here. He is not yet (in her reality) her husband. In her account of the kidnapping narrated immediately prior to the narration of the dream, she was taken from her mother’s side whilst awaiting the arrival of her groom and whilst surrounded by guests who did nothing to help – ‘so the nuptials were discovered and disturbed just like those of Attis and Protesilaus’ (4.26). The dream has revised and advanced the timing of abduction; the wedding has passed un-narrated and she is taken from her husband’s arms and the marriage bed instead.

The exposition of the kidnapping ended on the analogy and it’s an ominous pair of mythological exempla she selected for her groom: Attis driven to self-castration by the goddess Cybele; Protesilaus who left his new bride Laodamia to become the first of the Greeks to die at Troy (myths hopefully within the common knowledge of her audiences); more gloomy resonances evident here in her choice of attribute for her husband, the superlative adjective infortunatissimus ‘most unfortunate’. Infortunium was her noun selection to sum up her situation prior to divulging any details of content. Seeping into the dream, we find the adjective qualifying her husband, not the simple form, but another superlative; most cruel was the dream and most unfortunate the husband contained within it.

The pessimistic undercurrent carries on in viduatus est. Her absence due to being dragged away causes his being deprived of embraces, which is the closest her account gets to a negative expression. Her account, markedly passive in processes, is markedly positive in their expression and here the embrace-deprived husband responds to absence with operative positive action. He pursues, but he pursues viduatus, translated ‘deprived’ but more obviously ‘widowed’. Does her dreaming enactor fear for her own life? Is she projecting onto him a fear for her, of himself being/becoming a widow? Is it the feeling of the experiencing dreamer or the selection of a hindsight narrator nudging narratees to dark hypotheses? Possibly and plausibly all.

My second and third Verbalisations are made by the dream husband, both contained within a subordinate temporal clause that precedes the bandit killing him. utque clamore percito formosae raptum uxoris conquerens populi testatur auxilium – ‘And when the husband [Sayer] with an excited shout [Circumstantial adjunct, my cue to interpret as an utterance) lamenting the kidnap of his lovely wife [Verbiage]… ’.

Did he say ‘My lovely wife has been taken!’ or was the reported dream’s original Direct Speech ‘My wife has been taken!’ and ‘lovely’ is the embellishment of the speaker in the act of narrating? Whether the product of her conscious or unconscious, she is mind-modelling her dream-husband and ‘lovely’ is his embedded focalisation. It is how he views (or she thinks he ought to view) his wife.

Or the process could be simply behavioural, e.g. lamenting, he called for help. In that case we could read her kidnap as source/cause of lamentation but given than raptum is accusative in Latin and so direct object of the present participle, I’m personally inclined towards identifying it as a second Verbalisation. In my dream re-enactment, this husband makes two adjacent cries, a notification ‘My wife has been kidnapped!’ immediately joined by an appeal ‘Help!’; being as calling on the help of the people requires the proximity of the people, they enter my dream re-enactment as a ill-defined but present crowd of bystanders and enter my table above as implied receivers of reported utterances.

Mental & Behavioural Processes

| Process Type | SENSER | PROCESS | PHENOMENON | CIRCUMSTANCES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental (R) | bandit | stirred up | troublesome pursuit | |

| Mental (R) | bride | terrified | atrocity |

Rounding off the tabulation of processes then, there is one Mental process besides the one identified in the dream and that is the young woman’s narration of her state of mind upon waking – she was terrified by the dream. Of course all that happens within the dream follows on from the Mental process visa sum and does not actually ‘happen’. In the storyworld it’s a non-event, a narrated non-event that presents a distorted version of a previously narrated event, offered as explanation for a character’s current mental state and outlook. The speech ends appropriately then with two Behavioural processes which return us to her occasion for speaking.

| Process Type | BEHAVER | PROCESS | CIRCUMSTANCES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioural | bride | woke up | from sleep |

| Behavioural | bride | shaking |

With a sterner face she told the girl to explain why the deuce she was crying, or what had suddenly caused her to renew her wild wailing after being sound asleep. ‘I suppose you’re trying to deprive my young men of their sizeable reward from ransoming you. If you go on like this, I’ll have you burnt alive! I’ll just ignore these tears of yours; bandits don’t take much account of them.’

Metamorphoses 4.25, trans. Walsh.

The girl’s actorial motivation is to win over this aggravated old woman. She began her exposition with a request for the old woman’s sympathy, for her to show kindness and to contemplate the girl’s misfortune (4.26). She followed this with an account of her bridegroom, wedding day and abduction. The dream then presented a modified and darker version of that abduction.

Its discourse is neatly structured – a summary evaluation followed by scenic narration with a conclusion which confirms the opening evaluation. The young woman’s speech as a whole has a clear argument function (gain sympathy) and it is one which is successfully executed. Contributing to that success, I believe, are her consicous or unconscious stylistic choices e.g. the marked passivity whereby she presents as a victim of fate, feeling a helplessness from which she cannot escape even in sleep.

Taking a Cognitive Turn

So having mapped out the processes of our text according to the Hallidayan transitivity model, I’m now borrowing a little from Louise Nuttall’s approach in Transitivity, agency, mind style: What’s the lowest common denominator? To create her stylistic profile for reduced intentionality and control, Dr Nuttall reworks the Hallidayan mapping of material processes with a second model drawn from Langacker’s cognitive grammar. Nuttall then introduces six codings which make up her stylistic profile. moving (to summarise very briefly) from omission of patient [A], metonymic/meronymic actors [B], inanimate actors [C] through passive processes without actors [D] and nominalised processes [E] to perfective (atemporal or static) processes [F].

In CG, all six depart in one way or another from our prototypical construal of events in terms of a basic interaction between an agent and a patient along an action chain (Langacker, 2008: 356–357). These terms can be seen as parallel to Halliday’s ‘actor’, ‘goal’ and ‘process’,with the main difference residing in Langacker’s discussion of their embodied basis in an experiential prototype.

The protypical construal (or ‘canonical event construal’) is the most obvious instance of transitivity e.g. ‘The bandit killed her husband’ = agent (energy-source) → patient (energy-sink). Now what Nuttall does is apply her six CG codings delineating departures from the prototypical construal to selected texts and to manipulated versions of those texts. This CG model is also a cross-process model which avoids distinctions between e.g. Material and Mental processes and in doing so both ‘highlights the fact that not only doing, but also thinking, speaking and behaving can be more or less prototypically coded in terms of an underlying action chain’ and ‘allows broader patterns to be noticed in terms of construal, or the conceptualisations invited in readers.’

Nuttall goes on to put the theory into practice using online surveys on the texts to gather the responses of real readers on perceived mental state attribution (generating an impressive amount of data for analysis!) However, when attempting to map those codings onto this extract of the Metamorphoses what quickly became apparent was a lack of diversity in our text.

Sed ecce saevissimo somnio mihi nunc etiam redintegratur, immo vero cumulatur infortunium meum – in the introductory sentence, there is a passivation of process and an inanimate patient (misfortune) and (agent) dream. This is a stylistically deviant construal, wherein the speaking character relegates herself to disadvantaged pronoun mihi ‘for me’. The same pronoun in the same case reappears in the following sentence, emphasising her presence mihi ‘to me’ but also emphasising her lack of central control ‘to me I seemed to be dragged violently … ’. Dragged by whom? We could infer bandits from her preceding account of her actual abduction or supply it following the introduction of a bandit into the dream but as constructed, she is prominent as patient and the agent has been deleted. This process I would classify according to Nuttall’s codings as a D, passivised and agentless.

The pattern that emerges in the dream (treating processes alike) is one of prototypical construals featuring human actors (I called his name – he followed me fleeing, lamenting the kidnap, he called for help – one of the bandits killed my husband) separated by passive construals either of human patients without specified agents (husband deprived, husband struck) or of human patients with non-human agents (stirred up by outrage). There are none of the instances of meronymic, metonymic or nominalised agency noted by Nuttall in her graded analysis of Conrad’s The Secret Agent. But putting that disappointment to one side, there are still useful observations to be made. Here is my translation of the dream contents again, underlining ‘actions’ and labelling the prototypical construals A.

‘ … dragged violently from my home, my apartment, my bedroom, finally from my very bed and through trackless wastelands I called my unfortunate husband’s name [A].

And he, as soon as he was deprived of my embraces, still drenched with perfume, flowering with garlands, followed me [A] on the trail fleeing on feet not my own. And when with an excited shout, lamenting the kidnap of his lovely wife [A], he calls for the people’s help [A],

one of the bandits, stirred up with outrage of the troublesome pursuit, struck with a big rock snatched up by his feet* and killed my poor boy [A], my husband.’

* a very literal Latin rendering of this phrase involving two past participles would read ‘[killed] my having-been-struck husband with a big having-been-snatched-up rock.’ My translation makes for a less nonsensical reading but also creates an additional prototypical construal not present in the Latin text.

That chain of human actors is interesting in itself for one actor can be seen to supplant another. The young woman calls the name of the husband. He appears and replaces her as narrative agent until his own last act, a call for help. This introduces the bandit who assumes agency and acts to prevent the baton being passed further. At an impasse/creatively blocked, the young woman wakes up.

The husband, whose period of agency takes the greatest amount of Text-Time (see Measuring Arrows of Time), is the most schematized element of the text and his construal characterized by novel expressions (Langacker 2008: 55-7). He enters the narrative dripping with perfume and decked in floral wreaths. The groom deprived of the bride’s embrace can be seen as the protagonist of this brief narrative whilst its homodiegetic narrator, the dreaming young woman, casts herself as its damsel in distress, a bride who is lovely but has alien feet.

Evaluative and Affective Word Choices

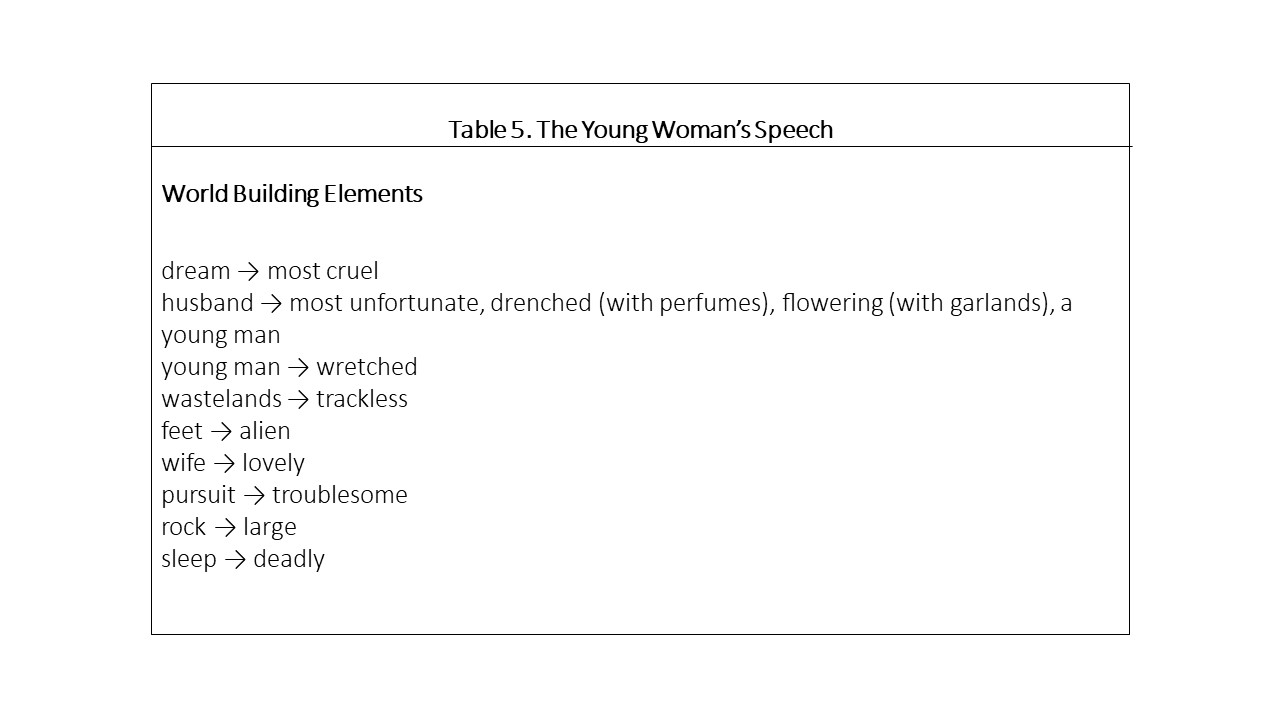

This brings us to the final aspect to consider before pulling these observations together, which is the density of evaluative language in the presentation of the dream. A notable omission from the list of processes mapped from this extract of text is the Relational process, at least if strictly determined by the inclusion of a verb linking carriers and attributes. There are certainly many attributes present as can be seen by the adjectives and adverbs emboldened in Latin text and English translation above and isolated in the table below which lists her dream World-builders.

These are the elements with which the young woman evaluates the dream-world and which in turn guide (manipulate) our own audience evaluations. It began in her framing of the dream with that preliminary qualification saevissimus ‘most cruel’ and continues as the dream contents expand into scene. Interestingly though that scenic expansion (in Text-Time) begins with a spatial contraction. Her narration of her abduction employs a zoom technique as she moves from exterior to interior with the range of vision steadily narrowing. The reader is invited to follow the path of the intruders – entering the house, moving to her apartment, into her room and finding her on the couch. The final location highlights for her narratees who she was (the bride) and the critical moment and place from where she was taken (the bridal bed). She has been taken by unseen agents and taken violently from a particular place and moment of joyful union.

Her calls for her husband emphasise the exceptional nature of her loss and the transformation of her fortune; the stolen bride is in her own words ‘most wretched.’ She calls him by name but does not share that name with her narratees. Instead, the man is identified by his relationship: ‘husband.’ Again the emphasis is on the marriage and on what he means to her. The dream version of the abduction takes her from the familiar and into the unknown as, in contrast to the specific locations which mapped the path from building to bed, she finds herself now in ‘trackless wastes’. She has been torn from what she knows into an empty and uncharted terrain; per solitudines avias – she is taking us on a journey though a land with no identifiers, a desert in which there is nothing to build. Her figures are lacking in ground.

This juxtaposition of familiar and alien persists in the details that accompany the husband’s appearance on the scene. Her opening expression contains the temporal adverbial expression ‘as soon as’ as she further reinforces the image of bride and groom and the instant of abduction. He is ‘drenched’ in perfume and wearing wreaths of flowers. He had only just a moment ago been in her arms. We see the groom through her eyes, brightly coloured and intoxicating, but immediately find his festive appearance contrasted with the foreign for she recognises him but not her own body. She is moving away from him, moving ‘on feet not her own.’ There is a psychological realism in her narration of her dream-form. She neither recognises nor can control her legs. Helplessness is again prominent, and with her own body working against her, she is being pulled away from her pursuing lover.

This coincides with her movement from actor to observer. She hears the ‘piercing’ cry (clamore percito) of his lament; an expression of grief which echoes her own wretched calls and binds the two lovers together. She looks at herself through the eyes of the husband. She identifies herself through him as ‘wife’. She is ‘lovely’ just as is the groom, beautified by his wedding apparel. His reported complaint within her direct speech that she was ‘kidnapped’ (raptum) confirms her earlier assessment of being ‘forcibly dragged’. Throughout her narration, they are husband and wife. They share similar actions and have similar appearances (with her reporting and focalising for him). The overwhelming emphasis in her discourse is of the shattering of a harmonious union and in the dream it is shattered by the husband’s death.

She provides actorial motivation for the act. It is one faceless bandit’s emotional response to the husband’s ‘troublesome pursuit’ of them and the manner of the death whilst detailed (he killed him with a big rock) is, in comparison with the preceding account, devoid of affective vocabulary. The husband is simply killed (interimo – ‘to take out of the midst, to take away, do away with, abolish’, L&S I). She does not (or will not) linger on that image whose horror jerks her out of sleep.

In closing she returns to her opening (completing the argument function with a rhetorical flourish) and the introductory ‘most cruel dream’ is re-cast and itself redoubled in elaboration as a ‘atrocious vision’, the creation of her ‘deadly sleep’. It is an explanation for her current emotional state which she emphasises again with her choice of vocabulary for her mental and physical state ‘terrifed’ and ‘shaking’. Her sleep is not strictly ‘deadly’ but a transferred evaluation of what the vision contains – the death of her husband and the premature end of their life together.

The reader of The Golden Ass might already be conditioned towards a pessimistic outcome. After all, this is not the first dream they have come across. Within the narration of the character Aristomenes (an intradiegetic narrator like the young woman) back in Book 1 was the short account of a dream in direct speech of his character-narrator Socrates (a hypodiegetic narrator). In that dream he had had his throat cut (and that was not far from the truth). From the misfortunes recounted in Book 2 by another intradiegetic narrator Thelyphron, we know that bad things and sleep do go hand-in-hand. In Book 8 when Lucius relates via the direct speech of her servant the fate of this young woman Charite and her lover Tlepolemus, the reader will realise the apprehension triggered by her dream was ultimately well-founded. But that perhaps is a narrative for another time.

References

Abbot H.P. ([2002] 2008) The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative, Cambridge.

Halliday M.A.K. and Matthiessen C.M.I.M. (2014) Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar,

(4th edn), London.

Langacker R.W. (2008) Cognitive Grammar: A Basic Introduction, Oxford.

Nuttall L (2019) ‘Transitivity, agency, mind style: What’s the lowest common denominator?’, Language and Literature 28(2): 159-79.

Simpson P. (1993) Language, Ideology and Point of View, London.

Simpson, P. and Canning, P. (2014) ‘Action and event’ in P. Stockwell and S. Whiteley, eds., The Cambridge Handbook of Stylistics, Cambridge: 281–299.

Stockwell, P. (2002) Cognitive Poetics: An Introduction, London.

Winkler, J. J. (1986) Auctor and Actor, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Possible Future Readings

As regards competing systems of narratology, what is extraordinary for me about The Golden Ass is not what it contributes to a general theory of narrative but the fact that it is, simply on the face of it, such a modern-seeming narrative about narratives. This wants explanation in the contemporary narratological style but not necessarily according to the rules of a single system. The bricks in my building have been scavenged from several sites: I only took what I could use for this project. Some of the best examples of narratology are focused on single texts (Barthes’s S/Z, Genette’s Figures III) rather than on the universal theory of narrative as such; this is the format I admire and find most congenial. I also regard critical totalitarianism as a real danger. In guarding against that, especially at the beginning in Part One, I knowingly take the risk of seeming eclectic to the point of being scatter-brained.

1. Analyse the stylistic deviancy observable in different levels of narration, e.g. the use of passives and evaluative language by the young woman as narrator compared with Lucius as narrator (of text). Do they have different stylistic profiles?

2. Continue the analysis of 4.27 with inclusion of the old woman’s response for comparison.

3. How does this dream presentation compare with previous presentations of dreams by other characters in The Golden Ass? How does it compare with presentation of dreams in Greek (and Latin epic) e.g. with Medea’s in Argonautica 3?

4. How do presentations of dreams found in Classical texts compare with e.g. those found in modern novels?

5. Apply the CG model to Medea’s dream.

6. Lexically grade instances of evaluative language in the Latin, though this along with attempting to build a Latin model of stylistic deviance would require a corpus.

Research interests include intertextuality, indeterminacies, reader-experience and reader-manipulation.