‘Breast is Best’? Rereading Catullus 64.18

‘What if the opening line had read, “Mommy died today”? How would we have seen Meursault then? Likely, our first impression would have been of a child speaking. Rather than being put off, we would have felt pity or sympathy. But this, too, would have presented an inaccurate view of Meursault. The truth is that neither of these translations—“Mother” or “Mommy”—ring true to the original. The French word maman hangs somewhere between the two extremes: it’s neither the cold and distant “mother” nor the overly childlike “mommy.” In English, “mom” might seem the closest fit for Camus’s sentence, but there’s still something off-putting and abrupt about the single-syllable word; the two-syllable maman has a touch of softness and warmth that is lost with “mom”’ (Bloom 2012).

Mother? Mommy? Mum? Ryan Bloom’s article Lost in Translation: What the First Line of “The Stranger” Should Be highlights the importance of first impressions, and how translation affects the reader’s expectations. Bloom’s anxiety is that all the proposed translations carry preconceptions that might influence the reader and generate an affinity (or lack of affinity) with Mersault. And in the course of reading his argument Aujourd’hui, maman est morte triggered in this reader a recollection.

illa, atque alia, uiderunt luce marinas

mortales oculis nudato corpore Nymphas

nutricum tenus exstantes e gurgite cano.

Cat. 64.16-18

The common elements here are an opening temporal deictic marker and the problematic translation of a noun. L’Étranger’s ‘Aujourd’hui’, Bloom argues, comes first for a reason. Mersault himself lives in the ‘now’ and the ordering of the opening line ‘offer[s] insight into Mersault’s inner psyche.’ The narrative of L’Étranger then begins ‘Today’. However, illa luce is not the first temporal marker in the text of Catullus 64. That is the quondam in the opening verse and it transports the invested reader to the time of Myth.

Peliaco quondam prognatae vertice pinus

dicuntur liquidas Neptuni nasse per undas

Phasidos ad fluctus et fines Aeetaeos…

Cat. 64.1-3

Once pine-trees born on Pelion’s crown

are said to have swum through Neptune’s clear waters

to the waves of Phasis and the territories of Aeetes…

That said, verses one to eleven are also preliminary exposition in summary and the poem’s first scene occurs at verse twelve when we shift from backstory as the Argo launches. It is this shift which contains the emphatic and provocative affirmation and denial: illa, atque <haud> alia, … luce.

On that day, and no other, mortals saw

the sea nymphs with their own eyes, bodies bare

as far as the breasts jutting out of the white rapid.

More on provocations shortly, but first the second common element which is not at all apparent in my rendering. Lines sixteen and seventeen are unproblematic for the translator (accepting the emendation haud in Mynor’s Oxford Classical Text). The difficulty occurs in the first word of verse eighteen when the reader stumbles on nutricum.

Some twenty seven years ago now, Richard Hunter’s very brief article ‘Breast is Best’: Catullus 64.18 was published in the Shorter Notes of The Classical Quarterly. It begins thus:

Catullus’ use of nutrices for the Nereids’ breasts in line 18 of Poem 64 is not perhaps the most important problem in the poem, but it is not without interest and may have significance beyond its narrow context. This ‘weird preciosity’ (Jenkyns 1982: 105) has been integrated into a wider reading by Francis Cairns (1984), who interestingly drew attention to Artemidorus 2.37-8 where to dream of Aphrodite emerging from the sea and naked as far as the ζώνη [belt/girdle] is a good omen for sea-travellers because her breasts are τροφιμώτατοι [most nourishing].

So how do we arrive at Jenkyns’ ‘weird preciosity’? Well, working back to front, the predicative adjective used in Artemidorus’ Greek text to describe Aphrodite’s breasts is the superlative of τρόφιμος (‘nourishing, nutritious’). A τροφός is a ‘feeder, rearer, nurse’ and that noun is derived from the verb τρέφω under whose meanings we find ‘feed or suckle an infant’(LSJ A III 4). Shift to the Latin and we have the verb nutrio ‘I suckle, nourish, feed, foster, bring up, rear’ and the noun nutrix ‘a wet-nurse, nurse’ under whose meanings we find (thanks to Catullus 64) ‘the breasts’ (L&S I B 2).

Now the puzzled Latinist could simply look up nutrix, spot that L&S entry, translate as ‘breasts’, keep calm and carry on. Except that ‘breasts’ is not the object signified but an object superimposed upon the signified through a series of connections made and to translate nutrices as ‘breasts’ glosses something odd, something that ought to strike the reader as odd and cause a processing pause. A better translation than ‘breasts’ is required to convey a sense of the innovation. Nourishers? This is Guy Lee’s rendering of lines 16-18.

In that and not another day’s light mortal eyes

Beheld the bodies of the Nymphs of Ocean naked

Far as the sucklers standing out from the white surge.

That’s certainly better at signposting novelty than my offering above. It is very difficult to keep the place of nutrices at the beginning of the verse in an English translation of tenus nutricum ‘as far as the…’ without garbling the line. In any case, I think Lee has managed to create prominence with the alliterative juxtaposition ‘sucklers standing out’. Whilst ‘beheld’ feels a little grandiose for uiderunt, this is Catullus at his most epic. What is also interesting from a translator who states attention to minutiae as a prime concern is ‘bodies of the Nymphs’. Nymphas is the direct object of uiderunt – mortales uiderunt Nymphas – ‘Mortals saw Nymphs’. nudato corpore is an attendant ablative clause – ‘naked in their bodies’. The crew of the Argo saw Nymphs, naked Nymphs! Well naked as far as their nutrices. Of course Lee knows this, so what’s the effect of making ‘bodies’ direct object and ‘Nymphs’ a possessive plural (mortales uiderunt nudata corpora Nympharum)? For this reader it underscores the oddity of nutricum and reinforces what it is that we’re being prompted to look at.

Perhaps we should be cautious in attaching too much prominence to word-order given the flexibility of the Latin language and I’m mindful here of Peter Stockwell’s comment in his cognitive poetic analysis of the Anglo-Saxon poem ‘The Dream of the Rood’.

You might even be tempted to read all sorts of stylistically significant meanings into the strange word-ordering, unless you know about Anglo-Saxon inflectional grammar and simply ascribe the grammatical flexibility to the demands of half-line alliteration.

Perhaps we should bear in mind the modern typographical layouts which facilitate stylistic significance and consider how the verses might look when line-breaks set by the width of a papyrus sheet and the handwriting of the scribe.

ILLAATQUEHAUDALIAUIDERUNTLUCEMARINASMORTALESOCULISNUDATOCORPORENYMPHASNUTRICUMTENUSEXTSTANTESEGURGITECANO

? Perhaps. Though if we had a better ear/eye for scanning dactylic hexameters we might note prominence without the aid of typography.

Each verse above follows the same metrical pattern: spondee, dactyl, spondee, spondee, dactyl, spondee. However, whilst the common strong caesura in the third foot is observed in verses sixteen and seventeen (after alia and oculis respectively), there is no room for such a pause in verse eighteen thanks to the stretched-out stretching (exstantes) of the Nymphs; nutricum tenus exstantes might cause a stumble with reading rhythm as well as processing sense.

Each verse above follows the same metrical pattern: spondee, dactyl, spondee, spondee, dactyl, spondee. However, whilst the common strong caesura in the third foot is observed in verses sixteen and seventeen (after alia and oculis respectively), there is no room for such a pause in verse eighteen thanks to the stretched-out stretching (exstantes) of the Nymphs; nutricum tenus exstantes might cause a stumble with reading rhythm as well as processing sense.

Another type of scanning is that which occurs in the cognitive linguistic analysis of action chains whereby cognitive input is either summarily or sequentially scanned by the reader.

Summary scanning is typically what happens when nominals are processed: attributes are collected into a single coherent gestalt that constitutes an element. The sun in ‘Look at the sun’ or ‘It’s a sunny day’ is a static feature that is summarily scanned. Contrast this with the sun in ‘The sun shone down’ or ‘The sun crossed the sky in a blaze of light’. Here there is sequential scanning which is typically what happens when an event or configuration has to be tracked. The difference has been likened to examining a still photograph and watching a film.’

Stockwell goes on to comment that in the action chain model there is an overlap when it comes to prepositional phrases. These can be either summarily or sequentially scanned; an overlap ‘which should also remind us that cognitive grammar is not about labelling parts of language but is about outlining reading processes that are applied to linguistic elements’ (Stockwell 2002: 66).

Verse eighteen contains two prepositional phrases either side of the present active participle exstantes: nutricum tenus and e gurgite cano. On my reading these phrases are not stative (despite the stative verb base sto) but part of a sequentially scanned dynamic process; ‘as far as their nutrices [Nymphs] extending out of the white foam’. The Nymphs that the crew of the Argo and the readers are looking at are mobile and need to be tracked.

Of course we can process sense much faster than it has taken me to explicate some potential lexical, metrical and linguistic difficulties, but lingering still, why nutrices? Why that way and not another way (Cur illa atque haud alia uia)? Why this trigger? Or if that takes us too close to intentionality, what is achieved by this presentation? What are we looking at? What are we being distracted from looking at?

The emerging of the nymphs from the water is also the emergence in the Latin language of the desirable world of Greek art, for the breasts of the nymphs are an allusion, a neologism appearing in the Latin language to give us a glimpse of the Greek.

Hylas and the Nymph(s)

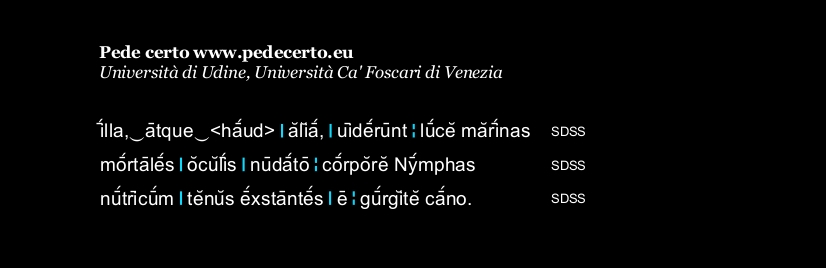

There were two triggers for the recollection of this opening scene in Catullus 64, and having made a case for the dynamic, the second trigger is itself stative. At around the same time as reading the New Yorker article, I visited the Manchester Art Gallery and took the photograph now set as the featured image – John William Waterhouse’s ‘Hylas and the Nymphs’. It depicts the moment of the Argonaut Hylas’ abduction by water-nymphs and according to its display label is ‘an evocation of sensual female flesh, an immersion into the deadly allure of the femme fatale’. In January the painting was removed from public display to ‘prompt conversation’ but returned shortly afterwards.

Sensuous female flesh. Why didn’t ‘Hylas and the Nymphs’ trigger the obvious recollection for someone whose PhD research focused on the Argonautica – the narrative of Hylas’ abduction in Apollonius’ Argonautica 1?ἡ δὲ νέον κρήνης ἀνεδύετο καλλινάοιο

νύμφη ἐφυδατίη. τὸν δὲ σχεδὸν εἰσενόησεν

[1230] κάλλεϊ καὶ γλυκερῇσιν ἐρευθόμενον χαρίτεσσιν·

πρὸς γάρ οἱ διχόμηνις ἀπ᾽ αἰθέρος αὐγάζουσα

βάλλε σεληναίη. τὴν δὲ φρένας ἐπτοίησεν

Κύπρις, ἀμηχανίῃ δὲ μόλις συναγείρατο θυμόν.

αὐτὰρ ὅγ᾽ ὡς τὰ πρῶτα ῥόῳ ἔνι κάλπιν ἔρεισεν

[1235] λέχρις ἐπιχριμφθείς, περὶ δ᾽ ἄσπετον ἔβραχεν ὕδωρ

χαλκὸν ἐς ἠχήεντα φορεύμενον, αὐτίκα δ᾽ ἥγε

λαιὸν μὲν καθύπερθεν ἐπ᾽ αὐχένος ἄνθετο πῆχυν

κύσσαι ἐπιθύουσα τέρεν στόμα, δεξιτερῇ δὲ

ἀγκῶν᾽ ἔσπασε χειρί, μέσῃ δ᾽ ἐνικάββαλε δίνῃ.

A.R. 1.1228-39

But the water-nymph was just now rising to the top of the fair-flowing spring. She marked him nearby blushing with beauty and sweet appeal, for bright in the sky the full moon was casting its rays at him. Cypris shook up her thoughts, and in her helplessness she scarcely steadied her heart. Still, as soon as he thrust the pitcher into the flowing water, leaned over to the side, and plentiful the water poured resounding in the ringing bronze, straightaway she drew her left arm over the back of his neck, rushing eager to kiss his soft mouth, and with her right hand she yanked his elbow, throwing him down into the eddy’s midst.

Almost all the agency here belongs to the unnamed nymph (Hylas’ being restricted to filling a jug of water). Sensuous female flesh? We observe what she does but we are not invited to look at her, at what she looks like. There is no description of her appearance, only of him as seen through her eyes with εἰσενόησεν signalling what follows as her focalisation. Caught in the moonlight he is beautiful and she wants him. The narrator provides information as to her emotional state with his observation on her physiological reaction. Seeing the boy sets her heart shaking (a reaction first attested by Sappho: τό μ’ ἦ μὰν | καρδίαν ἐν στήθεσιν ἐπτόαισεν ‘It sets my heart aflutter in my breast’, Sappho 31.5-6, trans. D’Angour). The reader can decide whether Cypris (Aphrodite) is directly responsible, is metonymy for desire, or both.

Differences due to medium include movement and narrative noise. All the gushing water and ringing bronze might muffle her approach, an approach which is both rapid and decisive. ‘As soon as he… straightaway she…’: she sees, she rises, she wrestles him under. This is not a seduction but a rapid strike. In the image the nymph has six accomplices, ‘all young naked girls who are nearly identical to one another’ (object description). Narrative currents might distort but in the static image still waters reveal. In both media, the nymph is the central figure but in the narrative she is the subject of action whereas in the image, framed by her six companions, she is the central object of our gaze. This brief compare/contrast is not to privilege the Apollonian version, only to admit that for this reader, the narrative presentation that the pictorial representation evoked was not to another version of the same episode but to the telling of another episode from another ‘Argonautica’ Catullus 64; a shift of medium from pre-Raphaelite art to neoteric Latin poetry.

Quoting from the gallery’s object description again: ‘The scene is viewed almost from above: the top of the picture shows no sky, only the brown tree roots and deep green foliage that line the water’s edge.’ Multiple figures, multiple naked nymphs, the view from above; in combination the angle, direction, and object of gaze took this reader back to the launch of the Catullan Argo and to nutrices.

‘I argue that the gaze – satisfied, frustrated, or interrupted – is the main thematic thread of the poem, and that this theme reflects the problematic relation of a belated poet and his audience toward the beautiful but lost world of myth on which they long to feast their eyes.’

On what are we longing to feast our eyes here? On what are the Argonauts feasting their eyes? Let’s step back a few verses before adding some more quotes and in what follows after, a splurge of self-plagiarism (ἐρρέτω αἰδώς).

illa rudem cursu prima imbuit Amphitriten;

quae simul ac rostro uentosum proscidit aequor

tortaque remigio spumis incanuit unda,

emersere freti candenti e gurgite uultus

aequoreae monstrum Nereides admirantes.

illa, atque <haud> alia, uiderunt luce marinas

mortales oculis nudato corpore Nymphas

nutricum tenus exstantes e gurgite cano.

Cat. 64.11-18

[the Argo] first in voyage initiated innocent Amphitrite.

And as soon as she ploughed the windy plain with her beak

and the water, whirled by oars, grew white with foam,

heads broke from the glittering water of the sound,

the marine Nereids, marvelling at the prodigy.

On that day, and no other, mortals saw

the sea nymphs with their own eyes, bodies bare

as far as the breasts jutting out of the white rapid.

What strikes about this passage is that the expected relation between sea and sailors has been reversed: the Argo ‘initiates’ the sea… Sailing is here a novel experience for the sea rather than the sailors. This paradox is sharpened by the word imbuit, used of the Argo’s initiation of the sea; the primary meaning of this verb is ‘drench’ or ‘wet,’ so one might expect the sea to be its subject not object.

The voyage of the Argo is like the voyage of the poet into a myth that he brings to life, penetrated, like a woman’s body, by his desire and conjured out of the froth of a language by the will to beauty (in this case, hairdressing).

That final remark in parentheses references Quinn 1970: 303, ‘torta suggests that the flecks of foam (spumis) produced by the twisting action of the Argo’s oars are actual curls (and the oars, if we like, the curling tongs).’ I must admit this ‘cosmetic’ reading of the launch is one that needed to be put before me, but once it’s there, for all the elegantly expressed metapoetic observation, the associated imagery of ships penetrating the sea and men making-over women leading into the literal ogling of nymphs reads as womanufacture.

Love poetry creates its own object, calls her Woman, and falls in love with her – or rather, with the artist’s own act of creating her. This is womanufacture.

Once the attentive reader of Catullus 64 progresses to the initial presentation of Ariadne in the poem’s inset narrative, the signs of womanufacture are neon bright, but perhaps they were already embedded in the transformation of Amphitrite (not standing in easy metonymy for the sea) from whence burst those naked nymphs. What are we looking at? What are we being distracted from looking at?

The poem began with a summary of the Argo’s creation and the Argonauts assembling. Summary gave way to scene when the Argo launched. Then came the nymphs to intercept the ship. Next Peleus spots Thetis amongst the nymphs, presented by the narrator as lust at first sight and an occasion which compels the narrator to cross worlds with an effusive address to his heroes before skipping on to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis.

The emergence of the sea-nymphs effectively scuttled the telling of a Catullan Argonautica. Their initial marvelling at the monstrum was a modest precursor to the fuller treatment given the heroes’ viewing of them, a viewing underlined by the emphatic placement and extravagant hyperbaton of marinas and Nymphas at successive verse-ends. The Argo is all well and good, but look Nereids! Something better had come along. Something with nutrices.

Another reader might not be distracted by what has been put in front of them. Another reader might be distracted by what has not.

The starting-point [of Hunter’s reading complications] is the familiar fact that the proem of Catullus 64 is much indebted to Apollonius’ Argonautica, in particular to the description of the start of the Argo’s journey at 1.540-58 and to 4.930ff. in which Thetis and the Nereids transport the ship safely past the Planktai. The Nereids’ bare breasts obviously recall and vary the bare legs of Apollonius’ Nereids (4.940).

Well, these are facts familiar and obvious for the Argonautica‘s reader. So bringing all readers up to speed…

Πάντες δ’ οὐρανόθεν λεῦσσον θεοὶ ἤματι κείνῳ

νῆα καὶ ἡμιθέων ἀνδρῶν γένος, οἳ τότ’ ἄριστοι

πόντον ἐπιπλώεσκον. Ἐπ’ ἀκροτάτῃσι δὲ Νύμφαι

Πηλιάδες κορυφῇσιν ἐθάμβεον, εἰσορόωσαι

ἔργον Ἀθηναίης Ἰτωνίδος ἠδὲ καὶ αὐτούς

ἥρωας χείρεσσιν ἐπικραδάοντας ἐρετμά.

A.R. 1.547-552

On that day all the gods gazed from heaven upon the ship and the might of men half gods, the best men then sailing over the sea, and from the highest peaks, the Pelian nymphs looked and marvelled at the work of Itonian Athena and at the heroes manning the oars.

In the Argonautica the launch is observed by gods and mountain nymphs. Catullus 64 omits the former and retains the amazement of the latter but transforms the subject as well as both the distance and the direction of the gaze. And the Nereids? Location, timing and circumstances have been fundamentally altered.

Ἔνθα σφιν κοῦραι Νηρηίδες ἄλλοθεν ἄλλαι

ἤντεον· ἡ δ’ ὄπιθεν πτέρυγος θίγε πηδαλίοιο

δῖα Θέτις, Πλαγκτῇσιν ἐνὶ σπιλάδεσσιν ἔρυσθαι.

A.R. 4.930-2

From all sides the maidens came to meet them, the Nereids, and from behind the goddess Thetis put her hand to the winged rudder to draw them amongst the reefs of the Planctae.

At the behest of Hera, Thetis leads the Nereids to perform a rescue, carrying the ship through the Wandering Rocks and facilitating the heroes’ return from Colchis. Our Argonautic relaunch has combined journey’s beginning with journey’s end and thrust this element to the fore. No nymphs looking down from distant Pelion but Nereids now in the waters around the ship. And crucially that proximity allows reaction. The men (and readers) can look in turn. The temporal marker illa… luce (64.16) pointedly echoes ἤματι κείνῳ (A.R. 1.547). On that day, they gazed. On that day, something changed. Behind the emerging Nereids a storyworld is being reformed.

In the Argonautica a third set of figures stand watching the ship leave the bay, the centaur Chiron and his wife who holds in her arms the infant Achilles and from the shore displays him to his father (A.R. 1.553-8): ‘The Iliad has as its theme μῆνιν … Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος (1.1). For the Argonautica this is a significant moment: Peleus leaves behind his son and Apollonius leaves behind the conventions of traditional ‘heroic’ epic’ (Hopkinson 1988: 185).

tum Thetidis Peleus incensus fertur amore,

tum Thetis humanos non despexit hymenaeos,

tum Thetidi pater ipse iugandum Pelea sensit.

Cat. 64.19-21

Then Peleus is said to have caught fire with desire for Thetis,

Then Thetis did not despise marriage with a man,

Then the father himself understood Peleus must be married to Thetis.

Change the object of Peleus’ gaze and change more than the story. Change the object and time unravels. Here the narrator offers names: one picked from the naked Nereids, one from the leering crew. Peleus remains in place, no longer looking back upon his son and martial epic but instead looking forward to his future bride incensus amore. A bride whom Apollonius revealed, shortly before the passage with the Planctae noted above, as being separated bitterly and permanently from her husband, whilst their son still an infant.

In Apollonius’ epic, stress is laid upon the separation of the baby Achilles from both his parents. At 1.553-8 he appears in the arms of his centaur foster-parents as the Argo sails past Pelion, and at 4.813 Hera pathetically refers to the baby’s longing for Thetis’ milk, τεοῦ λίπτοντα γάλακτος… Thus a specific reference to the nurturing power of breasts within a context recalling Apollonius’ Argonautica is, at the very least, tonally ambiguous. In Apollonius’ version, Peleus is left with nothing but despair, and Thetis’ breasts are all but unused.

Hunter’s note complicates a positive reading of the poem. Fitzgerald sees a point of ingress into a world of myth (and art). I’ve noted how nutrices on the one hand (and for an experienced reader) calls attention to its intertexts (and a radical rewriting of them) whilst on the other serves as a narrative device, a distraction conjured to cloak a temporal and thematic shift. It is a distraction which utilises the gaze, eroticised, male, objectifying, and leads to comments such as this: ‘as far as their breasts, gen. pl. with the preposition tenus, is nearly pictorial, and helps explain Peleus’ sudden love-at-first-sight’ (Garrison 1991: 134). ?

The Catullan narrator will indulges in more extensive voyeurism with the introduction and depiction of Ariadne as an erotic image on a cover draping the wedding couch of Peleus and Thetis; a depiction on which Alison Sharrock has observed, ‘There can be no denying the erotic connotations of Ariadne’s unravelling, whether as text or as woman, nor of the objectifying tendencies of her captured picture in the coverlet. This is a classic case of womanufacture’ (Sharrock 2000: 25, n. 48). Further investigation of Ariadne will require a second post, though in the meantime the interested reader need only search Ariadne Abandoned using their favourite search engines or social media hashtags to see the common elements of her ‘unravelling’. And no, I still don’t have a better translation for nutrices.

References

Fitzgerald, W. (1995) Catullan Provocations: Lyric Poetry and the Drama of Position,

London.

Garrison, D. H. (1995) The student’s Catullus, London.

Hopkinson, N. (1988) A Hellenistic Anthology, Cambridge.

Hunter, R. (1991) ‘“Breast Is Best”: Catullus 64.18’, CQ 41: 254-255.

Quinn, K. (1970) Catullus: the poems, London.

Sharrock, A. R. (1991) ‘Womanufacture’, JRS 83: 36-49.

Sharrock, A. R. (2000) ‘Intratextuality: Texts, Parts and W(holes) in Theory’ in A. Sharrock and H. Morales, eds., Intratextuality: Greek and Roman textual relations, Oxford: 1-39.

Stockwell, P. (2002) Cognitive Poetics: An Introduction, London.

Further Reading

Adams, J. (2005) ‘Neglected Evidence for Female Speech in Latin’, The Classical Quarterly 55: 582-596.

Fontaine, M. (2008) ‘The Lesbia Code: Backmasking, Pillow Talk, and “Cacemphaton” in Catullus 5 and 16’, Quaderni Urbinati Di Cultura Classica 89: 55-69.

Michalopoulos, A. (2009) ‘Illa rudem cursu prima imbuit Amphitriten (Catul. 64.11): The Dynamic Intertextual Connotations of a Metonymy’, Mnemosyne 62: 221-236.

Further Reading on the Web

Presenting the female body: Challenging a Victorian fantasy

The Breasts that Launched a Thousand Ships

Research interests include intertextuality, indeterminacies, reader-experience and reader-manipulation.

![John William Waterhouse [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Featured Image @adynamicreader - ‘Breast is Best’? Rereading Catullus 64.18](https://adynamicreader.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/John_William_Waterhouse_-_Hylas_and_the_Nymphs.jpg)